| Let’s dig back. Let’s dig w-a-a-ay back, to North

Carolina’s original Lord Proprietor. Some of you are probably smirking

right now—“Lords proprietors, you

monkey! There were five—Lord Craven, Lord Carteret, Lord Larry, Lord Curly and

the Earl of Moe. But they were not the originals. King Charles I (reigned 1625-1649), like his son, had favors to bestow and little sense of the value of American real estate. His “Atturney Generall” (spelling was creative in those days) was Sir Robert Heath, a fellow who, by looking at his picture, wore a modified “Flying Nun” hat and one of those high, ruffling collars that is evidence of how much fashion designers have hated mankind from the beginning of time. |

When you were granted

land like that you were expected to develop it: exploration, settlements, courts, Wal-marts, the

whole works. But Sir Robert turned out to be a major couch potato and for

twenty years did absolutely nothing with his holdings.

Along about 1642 a fellow named

Oliver Cromwell led an English Civil War that resulted in Charles I’s head

rolling across the floor (1649). Not wanting to stain his neck ruff, Sir Robert

fled for France.

After Charles II gained his throne in 1660, Heath’s descendants tried to reclaim Carolina, but Charlie would hear nothing of it, declaring them ineligible since Heath had fled the country. Besides, he was looking to reward some of his own friends and supporters who’d helped him regain his throne. Hence, he took that original charter and awarded it to a party of five in March of 1663—those proprietors whose names are honored by multiple counties, rivers and sounds today.

This column originally ran October 27, 2008.

Contact me at: newbernhistory@yahoo.com.

| Happy birthday, North Carolina! Well, sort of. Our beloved land of the Tarheels is sometimes called the state without a birthday, because no one can quite figure out when the first European threw down his hat and settled here. |

It’s a shame those Roanokians got so badly lost; if at least a few folks had hung around then--bang!—there’d be our birthday, jam-packed with drama that few states could beat. I mean, come on: Indians and explorers and a girl with a name like “Virginia Dare.” What writer wouldn’t kill to come up with a name like “Virginia Dare”…?

Virginia had Jamestown. New York had – well – New York (though it went by “New Holland” then). South Carolina had Charleston, no doubt, and Georgia rose up from its Savannah. Solid birthdays, those: no battles over where the capital will be this week. The people hung around, planted their fields and stayed to tend them.

One must allow that North Carolina was always at a disadvantage. Everybody else had nice little bays and rivers; North Carolina was stuck with the Outer Banks and its shoals – sandbars hungrier than sharks, lying just under the surface and waiting to chew the keel off the bottom of every unwary boat. It made for great beaches, but 17th century folks were not sun worshippers. Nobody wanted to settle here; heck, even the Lost folks had been ingloriously dumped, against their wishes, by a privateer captain who wanted to get back to making profits.

But eventually some European had to settle the place. After all, North Carolina is a huge stretch of land between Charleston and Williamsburg to remain caucasianless. It was good land, if one could just get past the bogs: full of turpentine-producing pines, rich farmland, and lots of Native Americans with whom to cheat, enslave or trade.

Enter one Nathaniel Batts. True, he did not have an inspiring name like Virginia DARE – in fact, his handle was reminiscent of belfries and bad mental states. But he had the advantage of starting out in Virginia (hence no danger from shoals), and an eye that appreciated the value of Indian furs. He set up a trading post along the Albermarle Sound (on the Pasquotank River to be exact) and received his titled deed from Virginia on September 24, 1660.

True, you history teachers and trivia buffs will point out that Europeans had been drizzling into the land for many years before this, and, yes, a “post” doesn’t quite have the shine of a “colony.” But old Nat left his footprint in the form of an official deed, and the deed declared a bona fide place and date. What more do you need for a birthday?

So on the 24th, honor the day: lose some relatives in the back yard (don’t forget to give them a pen knife so they can carve on a tree), or maybe invite a Tuscarora to lunch. Then make a cake with 348 candles and sing happy birthday to your state.

Originally ran September 22, 2008.

Contact me at: newbernhistory@yahoo.com.

I should note, as I insert this column, that at least one reader gave argument about my choosing date. Richard Smith, for instance, pointed out that Mr. Batts's deed had been granted by Virginia, that notoriously uppity colony to the north. He pointed to the charter of North Carolina to the five Lords Proprietors on April 1, 1663. But honestly, who wants to celebrate their birthday on April Fool's day? (We could also go back to the first charter--when Carolina was first called "Carolina" given by the previous King Charles to Sir Robert Heath on October 30. The problem for Mr. Heath is that it never occurred to him to develop his claim... and so he lost it.)

But Mr. Smith was not done: he rejected the charter (on the grounds that Charleston got the capital, since Mr. Batts didn't have enough room in the parlor for a general assembly to meet). He suggested, instead, a much more recent date: January 24, 1712. This was the day that Queen Anne's cousin, Edward Hyde was appointed "governor of North Carolina." The argument, see, is that this is the first time that North and South Carolina were seen as separate entities.

I confess these are all good arguments. September 24? October 30? April 1? January 24? I'll leave it to you to choose the day to light your candles.

1663: John Locke, Lord Cooper and the Carolina Constitutions

It may interest you to know that John Locke had some direct ties to North Carolina. Meanwhile, it may terrify me to suspect that a lot of you think I mean a

character on television’s “Lost.” So—basic class to start with: John

Locke had never ridden a wheel chair, and was not bald or fond of knives. But he was one of the greatest philosophers of modern times.

His ideas on liberty and government had much to do with bringing our

Constitution (and the Revolution) about. So think about Mr. Locke, and be

proud! John Locke (1632-1704) (birth-death statistics give historical columns undeniable weight) was also the tutor, advisor and very dear friend of Anthony Ashley Cooper, Early of Shaftesbury—one of the eight lords proprietors of Carolina. So: what, some of you are wondering, is a lord proprietor? Put on your studious expression and nuke some tea, because we're about to embark on a class lecture: | .png) John Locke and his locks (picture in the public domain). |

North Carolina was a late-term child in the American colonies. The Carolinas were at first awarded to eight men, Lord Ashley included (another was Lord Craven—sound familiar, Craven County residents?) back in 1663. These men had helped King Charles II regain the throne his father had lost (along with his head). This Proprietary Eight controlled the land for their pleasure and profit, answering only to the king. From their homes across the sea they raked in the profits of all this real estate we live on today.

Finally, in 1729, the king decided

it was time to make Carolina a royal colony, and he bought out the

proprietors—all but one, anyway; but that’s another story.

Locke, who was also a fine doctor,

cured Lord Ashley of a liver infection and they became fast friends. The young

philosopher moved into the earl’s home where he had little to do but attend

liver ailments, improve his Whist skills, and think. Of such things great philosophy is born.

Both men held a deep love of

religious toleration. In 1669, they sat down to write the Fundamental

Constitutions of Carolina. This constitution had a number of far-seeing,

ahead-of-their-time elements including elections by secret ballot and granting

civil and political rights to dissenters—namely anyone who was not a member of

the Church of England. It was one of the earliest and broadest declarations of

religious freedom of that time—and for some time to come.

I should note, I guess, that

Carolina never adopted them. But many of their principles were.

Unfortunately Lord Ashley made some political blunders in his life that resulted in his fleeing to Amsterdam where he soon dwelt in an English merchant’s home. Locke also spent time in exile (he was not fond of Charles II in the end, nor was Charles fond of him) though he returned when William of Orange became king and lived out his days in beloved England.

This column first ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on December 17, 2007.

1672: George Fox Visits North Carolina

When it came to missions it was the Quakers, not the Anglicans, who first felt their oats...

George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends (Quakers), brought his Gospel to settlers and Indians in 1672. | My rapidly-being-educated daughter has pointed out that not all settlers to the American shores came for religious freedom. The 1607 Jamestown Colony, for instance, was a purely commercial enterprise. It can be argued that there was a trace of a thirst for religious freedom behind the founding of New Bern: the many Palatines who were part of Christoph Von Graffenried’s settlement were, after all, refugees driven from the Rhine because of their faith. But their flight for religious freedom ended in England, not America. The step that brought them here had more to do with politics (“What are we going to do with all these refugees?” shouted Parliament) than piety. William Saunders, in his preface to the first volume of the Colonial Records, agrees: “It is perhaps a very flattering unction that we lay to our souls in supposing our State was settled by men seeking religious freedom, but unhappily there seems to be no solid foundation for the belief. So far as we can see, the moving causes of immigration to Albemarle were its delightful climate, magnificent bottom lands and bountiful products. “ |

Meanwhile, south of the Albermarle, the cash-strapped Baron Von Graffenried came seeking wealth through silver mines and silk. He even brought German miners along for just that purpose. They never dug any silver up, by the way. And the mulberry trees didn't really take.

A mind for mining does not mean our founders weren't religious, however. Visit Jamestown and learn what happened to those who dared skip church—or read Von Graffenried’s dreams of a central church in New Bern.

North Carolina had its share of missionaries and it may surprise you to learn that among the earliest were Quakers.

We think of Quakers mainly as the funky guy on the oatmeal box, or maybe as Richard Nixon’s ironic religion. Co-founded by George Fox in the 17th century, Quakers turned their backs on the traditional church. Subjects of persecution, they believed that every man has an “inner light” – the presence of God in him—in other words, that the Deity speaks directly to each person. They were devout and peace loving. Women preached as well as men. Their views toward tolerance and fairness were powerful (witness William Penn) and their staunch pacifism would ultimately bring North Carolina grief in the Tuscarora wars.

It seems odd to think they would have been a step ahead of the mother Church of England, but they were. In fact, George Fox himself trod the Carolina soil in September 1672. In his journals he spoke of traversing “woods and… many bogs and swamps.” Yup: that's North Carolina. He visited Nathaniel Batts, “who called himself Captain… and had been a rude, desperate man,” and who was one of the first known settlers in North Carolina (see the column above).

“Not far from hence we had a meeting among the people,” Fox wrote, “and they were taken with the truth; blessed be the Lord!” Fox then met the governor (probably John Jenkins) and his wife. Here, a cantankerous doctor argued with him about the “the Light and the Spirit of God,” claiming Indians did not have it. “Whereupon I called an Indian to us,” Fox recalled, “and asked him whether when he lied, or did wrong to any one, there was not something in him that reproved him for it. He said there was such a thing in him, that did so reprove him; and he was ashamed when he had done wrong, or spoken wrong. So we shamed the doctor before the Governor and the people.”

Fox had only good to say about the Native Americans he met, by the way.

The Quakers were highly effective in North Carolina. They came finding no more than one or two fellow Friends but their message of peace resonated with a troubled and endangered people. By 1709 they made up a tenth of the population.

This column originally ran on September 29, 2008.

The Founding of New Bern: Some Opening Thoughts

The story of our founding is complex and fascinating. It goes well beyond the arrival of some Swiss baron and his flock of Palatines and a nasty little Indian war.

We New Bernians tend to see our founding in terms of two-dimensional figures and simplified events. We take our founders and cast them as villains or heroes in a bad dime novel. I recently read part of a play presented in 1960 as part of a New Bern founding celebration: in it, John Lawson’s character stomped around all ill-humored, grunting like a bear; Baron von Graffenried went about sounding godly and majestic like an understanding angel too good to be true. The noble Savages did their noble-savage thing, sounding like Tonto in a vintage Lone Ranger film. They loved Graffenried and slew the Evil Lawson.

But things were actually quite a bit more complicated (and so were the characters involved). Lawson was not so evil; only DeGraffenried’s documents paint him as being so; Graffenried had his moments when he was a good distance from saintly.

There were other people (and peoples) who figure into our founding as well: a French Huguenot colony on the Trent, for instance. Carey’s Rebellion, which weakened the colony in a manner that encouraged the Indians to take to war. There was Thomas Pollock (to whom a financially-wrecked Graffenried mortgaged the town) and William Brice, a powerful English settler already in the region when the Palatines arrived.

We’ll take a few columns to look at, not just John and the Baron, but other interesting characters and events directly or peripherally involved with New Bern’s creation, and we’ll also examine the lives of New Bern’s first residents—the Neusioc Indians and their relatives the Tuscarora. You may be surprised by some of the events as they actually took place.

(This originally ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on January 4, 2010)

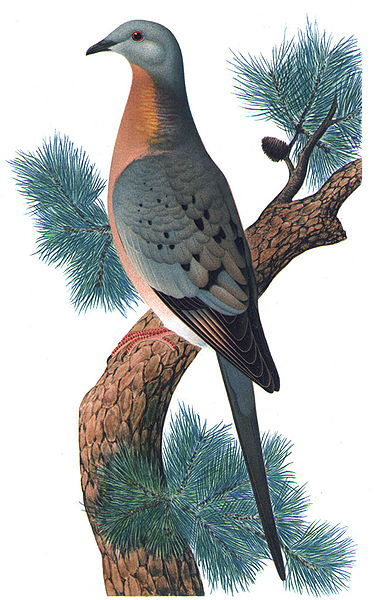

1708: Passenger Pigeons in North Carolina

The last passenger pigeon was named Martha. She died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden 1914, age 29. That’s pretty pathetic, considering that, at one time, these amazing birds were estimated to number in the billions. This particular breed of squab was fairly large, at 17 inches’ length. And, apparently, tasty. When the Europeans arrived, the passenger pigeons’ days were numbered. They were slaughtered by the thousands. For a time men actually made a living traveling to pigeon breeding grounds and killing them for market. By the mid-1800s they were thinning out. Between overhunting and deforestation, by 1914, they were gone. The eastern seaboard Indians—ours included—were fond of these guys as well. Sometimes their winter hunting camps were aimed as much as putting them near the pigeons’ nesting grounds as any other game. They used the pigeons for meat and even as a kind of butter. Explorer John Lawson wrote about his first experiences with passenger pigeons: |  |

[They] were so numerous in these Parts, that you might see many Millions in a Flock; they sometimes split off the Limbs of stout Oaks, and other Trees, upon which they roost o' Nights. You may find several Indian Towns… that have more than 100 Gallons of Pigeons Oil, or Fat; they using it with Pulse, or Bread, as we do Butter… The Indians take a Light, and go among them in the Night, and bring away some thousands, killing them with long Poles, as they roost in the Trees. At this time of the Year, the Flocks, as they pass by, in great measure, obstruct the Light of the day. You’ve got to admit, that’s a lot of pigeons. The ground beneath the trees, where they roosted, was covered by a half-foot layer of dung. Think of parking your newly-waxed car in the shade and discovering that the next morning!

And, Lawson avowed, this was only a small portion of their population: in 1701, when he was exploring the westernmost part of the Carolinas, he saw “infinite Numbers of these Fowl…[that] would fly by us in such vast Flocks, that they would be near a Quarter of an Hour, before they were all pass'd by; and as soon as that Flock was gone, another would come; and so successively one after another, for great part of the Morning.”

It is sad that spectacles like this can only be experienced through history—and that we are the reason this is so.

This column first ran on January 21, 2010.

1709: The Rise of the Palatines

They lived in tent cities across England—political refugees, crowing London, causing fear and enmity through their needs for care and jobs. They were the Palatines. Where did they come from? They were religious and political refugees, a Germanic folk who hailed (and fled hails of bullets) from the Rhine River in what is now Germany. Most were staunch Protestants—followers of that inkpot-throwing fellow Martin Luther—farmers living in a land fertile in both soil and blood. The 30 Years’ War (1619-1648) had not

been kind to them. The seriously Catholic Sun King, Louis XIV, would be no

kinder, overrunning the territory and persecuting whomever he could find during

his War of the Palatinate (1688-97). Just as the battered people were picking

up those pieces, the War of the Spanish Succession succeeded in further

depopulating the land; then 1708 brought a winter crueler than Spanish steel. |  This old woodcut shows Palatines in migration from their homeland. |

England’s Queen Anne was as pro-Protestant as Louis XIV was pro-Pope. Her heartstrings were tugged, and her admiration of the Palatines’ commercial possibilities whispered in her ear. She offered residence to any refugees who could reach England’s shores. They came—with a hopeful vengeance; the first thousands on May 3, 1709. By November more than 32,000 crowded the streets and shops and courts, speaking their harsh German tongue. The city was in alarum, and Parliament—never a fan of the queen—was in a rage. She had to do something with all these people! Telling them to go back home was not an option—queens must save face. But keeping them in town wasn’t any better solution.

She decided that, if immigration

had been bad, maybe emigration would

work. Four thousand were shipped north to Ireland, a land burgeoning with

hostile Catholics and needing more Protestants friendly to the crown. That

still left an unhealthy number in town.

Enter a Swiss socialite in

desperate need of funds.

His name was Christopher

DeGraffenried (or VonGraffenried, take your choice). The son of a Swiss

nobleman, he was known to be a spendthrift who had gallivanted about the

European courts and was now hoping to beat his debts by founding a town in

North Carolina where, he’d been led to believe, he would gain wealth in the

cultivation of silkworms and silver mines. It would be named New Bern.

He had a handful of roustabouts and

miners to found his town, but was in desperate need of more labor.

Anne must have thought God had sent

her a solution to all her ills: she would pay their passage. London’s

over-population of refugees would be relieved. The Palatines’ suffering would

end.

But in reality, it was just about

to begin…

It was on a cold, blustery January

in 1710 that a German-speaking minister in Gravesend intoned parting blessings

upon 650 Palatines. I have no evidence of that day being cold and blustery—but

we’re talking England here, so I’m it’s a pretty safe bet.

Their leader, Baron Christopher

DeGraffenried did not sail with them: he would come later. But he sent the

highly-competent John Lawson, surveyor-general of Carolina to settle them

in. Each man was to receive 300

acres of land at minimal rent; tools; a cow and two pigs; and a year’s worth of

food to hold them till harvest (the settlers, not the cows and pigs). But

theirs would be a long and miserable thirteen-week voyage of foul winds and

wicked storms. “This, along with the salt food to which the people were not

accustomed, and the fact they were so closely confined,” DeGraffenried would

write, “contributed very much to the death of many upon the sea.”

“On the twenty-sixth of February,”

Hans Ruegseger, one settler, sadly wrote home, “my son Hans, with a great

longing for the Lord Jesus, died.” One can imagined the melancholy of that

pitiful crossing.

Less than half were still alive

when they arrived at Virginia in April, where a French privateer, wanting to

prove that sometimes you just can’t win, robbed their best-stocked ship blind

and even left some of the Palatines naked in its wake.

Virginia’s Governor Alexander

Spotswood watched the survivors for a few days as they continued to dwindle through

death, then sent them off, overland, to the Albemarle district, where Thomas

Pollock, one of Carolina’s wealthiest and most powerful men, resided. He sold

them provisions and a boat and hurried them on their way.

In New Bern at last, they hunkered

down in misery to await DeGraffenried’s arrival.

He came on September 10 and stared

slack-jawed at the refugees on shore. “From lack of provisions they were…

compelled to give their clothes and whatever they possessed to the neighboring

settlers for food,” he would later write. “The misery and wretchedness were

almost indescribable, for, on my arrival, I saw that almost all were sick, yes,

even in extremity, and the well were all very feeble.”

DeGraffenried wrote that he and the

additional Swiss settlers with him set to work improving their condition:

”Within eighteen months they managed to build houses and to make themselves so

comfortable that they made more progress than the English inhabitants in

several years.”

But fate was weaving a web of

disaster: between elements of political rebellion, merchant greed, Indian

unrest and DeGraffenried’s own failings, the vast majority of these early

settlers were doomed.

This article first ran as two columns in the New Bern Sun-Journal on December 30, 2007 and January 7, 2008.

1714: The Battle of Fort Neoheroka

It is one of those uncomfortable things to admit—that the Tuscarora War of 1711-15 was fought over slavery. Yes, there were other important

factors: anger over European intrusion, dishonest traders, and just-plain

clashes of cultural life-style. But the thing that really grated with the

Tuscarora elders and their allies was the kidnapping of their wives and

children who were off as slaves to other colonies. In June, 1710, they sent the

Pennsylvania assembly protesting enslavement by local settlers, and asked this

bastion of Quakerism to refuse to purchase such slaves. |  The type of longhouse the Tuscarora dwelt in. |

The Indians had wisely chosen the start of their war in September, 1711, when the colony was torn apart by political intrigue, disease and near famine. Weapons were few, and numerous Quakers in the colony refused—as a religious tenant—to take up arms in defense of the colony. To make a long story inadequately short, the Tuscarora opened the war with a surprise attack that left 140 men, women and children dead. Inadequate to itself, North Carolina turned to Virginia, which refused to help unless the colony surrendered land, and then to South Carolina, which sent Colonel John Barnwell with an army of a few white men and several hundred friendly Indians. He fought the Tuscarora to a standstill and signed a truce in 1712. The war went on.

In 1714 Colonel James Moore arrived

from South Carolina, 33 whites and 900 Cherokee and Yamasee Indians in tow. By

now the Tuscarora had built a significant fortress called Neoheroka along

Contentnea Creek, near present day Snow Hill. It was palisaded—protected with

upright log walls, and had access to the creek so that the Indians could better

survive a siege. The fort also had houses and caves inside—as well as a fairly

elaborate tunnel system – reminiscent, perhaps, of those tunnels our friends

the Viet Cong were so fond of in the Vietnam War.

Colonel Moore's forces arrived on March 1 and prepared a siege. Unlike the days of 1711, the colonial forces were now well armed and their enemy worn down. The Tuscarora were facing a bloody and ironic end.

Neoheroka was an

impressive fort for its day, built by its Indian defenders from a tradition of

older forts and some “new” technology learned from observing colonial

fortresses. Archeological digs have determined the palisade wall was about 360

feet in length, and that the compound included 17 bunkers to shield its

noncombatants during war.

It held in the

neighborhood of a thousand souls—but most were women, children, and elders too

aged to take part in a fight. Most of the men were armed with tomahawks, knives

and arrows.

For twenty days they had been

besieged by Colonel Moore’s mixed-bag army of roughly 950 Indians, South and

North Carolinians, all under the command of Colonel James Moore. It was the 20th

of March, and the final three-day battle was about to begin. These colonial

forces were well-armed, well-supplied and determined.

For days the Europeans had been

preparing for the fight: a trench had slowly zig-zagged its way toward their

palisade walls. Under its protection, they constructed both a blockhouse and a

battery—both of which rose higher than Neoheroka’s walls. They also dug a

tunnel from the trench to the wall so they could have the option of blowing a

hole there with explosives.

To the sound of a trumpet the

battle began in earnest on March 20. It raged for three days. On March 23 the

fort was breached and the slaughter in full began. Many were cornered in their

bunkers and killed with grenades and musket balls. Moore ordered the fort

fired, and numerous men, women and children were burned alive. Another 170 were

killed outside the walls.

A few Tuscaroras managed to escape

using underground tunnels. Moore rounded up 400-odd survivors and sold them

into slavery in South Carolina—consigning the Indians to the very fate that was

a primary cause of their going to war.

The battle did not end the

Tuscarora War—it would hobble on until February 11, 1715 when the Indians

agreed to peace in exchange for a reservation at Lake Mattamuskeet.

Today the Fort Neoheroka site is

private farmland and, as you may imagination, the Tuscarora are working to get

it claimed and protected as a historic site. Its many victims lie buried, their

skeletons preserved by the hardening of Colonel Moore’s fires, making it one of

the largest mass burial sites of Native Americans in the nation.

This column first ran in two parts on March 16 & 23, 2009, in the New Bern Sun-Journal.

1729: The Birth of William Tryon

Above: The reconstructed replica of William Tryon's mansion and government building at Tryon Palace Historic Sites and Gardens, New Bern.

Today, June 8, is the day that all good New Bernians should turn toward the Tryon burial site at Twickenham and sing “Happy Birthday.” It was on this day in 1729, 280

years ago that William Tryon was born at Norbury Park, Surrey, England. Without

him we would have no Tryon Palace or Tryon Palace Seafood here in town, and

certainly no lovely Tryon Park in beautiful downtown New York. See it and tell

them I said “Hey.” Much of New Bern today seems built around the aura of this colonial governor. He was here only a year and yet that one year was highly influential in our town’s and state’s history. His family, probably of Dutch descent, was long in the tooth in England: his ancestor Peter Tryon, a wealthy Flemish man (what do you call a Flemish man? A Flem?) fled the tyrant Duke of Alba in 1562. Other Tryons had been in the British Isles since 1066. Through his mother, Lady Mary Shirley Tryon, he was descendant of the Earl of Essex, a pet of Queen Elizabeth. His father’s name was Charles (whose portrait hangs in the master bedroom at Tryon Palace), who would | die in his 40s. William was one of several siblings: Charles, Robert and James were older; Mary Sophia and Anne were younger. It would be difficult to write a long column on his childhood, for we know almost nothing about it. He was well-educated and soon developed a love of books (he collected what was, for the time, an immense library). He took to the military, becoming lieutenant of the First Regiment of the Foot Guards in 1751 (one wonders if their guns were primed with Desinex powder? And was their surgeon named Dr. Scholl?) and was later promoted to lieutenant colonel. He showed bravery in action in 1758, during the Seven Years War, when he helped oversee a withdrawal from the beaches of St. Cas Bay when the British were overwhelmed by French defenders. A secret of English politics was: “Marry well.” Although he sowed some wild oats that resulted a love child named Mary Stanton (the mother’s name was Elizabeth), he settled down in and married the heiress Margaret Wake in 1757. It was through her connections that he became governor of North Carolina. While he remembered Mary in his will, he was apparently entirely loyal to Margaret throughout their lives. This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on June 8, 2009. |