Tabernacle Baptist is Built on the Homesite of a former Slave

Moses P. Kennedy was born a slave and, after his manumission, lived on the land where Tabernacle Baptist now stands.

“From slavery to freedom in Christ.” Perhaps this ought to be

the motto for Tabernacle Baptist Church, since their building rests on the site

of a former slave’s home. Moses P. Kennedy was born

a slave, in the home of antebellum statesman John Stanly. He was, in fact,

personal body servant to John. His

master must have been pleased, for he eventually set Moses free. His

manumission application said that “Moses could ever be relied upon as a

faithful servant.” Moses must have been a

mild-mannered sort: Colonel John D. Whitford spoke fondly of him, and Whitford

was a man of his time: an “admirable” negro was one who “behaved himself… well”

(read Whitford’s Home Tales of a Walking Stick, page 140). Moses was “deemed an honest citizen by those people who knew him for two generations and too was as courteous as Chesterfield himself, always doing the right thing at the right time…” Except for one little lapse in his old age when he married “a young colored girl who, without unnecessary delay thereafter seized all in sight she could carry off and then left for parts unknown.” Alas, as long as there are lonely old men there will be gold diggers. For a time--the very time of the unfortunate marriage, in fact—Whitford was Moses' landlord. The old colonel used him as a messenger to one Weldon N. Edwards, a friend (who had also been a friend of John Stanly) and judge living in Ridgeway. The judge took a liking to Moses as well and expressed his pleasure by requesting Moses' tintype and a letter from his hand. |  Tabernacle Baptist on Broad Street today. |

Edward Stanly, son of John, who spent a brief and disastrous term as Lincoln-appointed governor during the Civil War (Lincoln thought that Stanly would bind the state’s wounds; instead he was declared a traitor), willed a home to Moses’ use so long as he lived. This was the home at the corner of Broad and George Streets, sold some years after his death to Tabernacle Baptist Church.

This column originally appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on March 9, 2009.

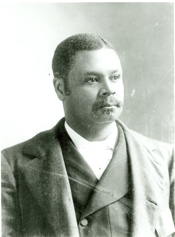

1882: James O'Hara, Congressman

Born black and illegitimate, he still rose to one of he highest offices of the land, representing the post-war South.

| He was born a black man in 1844—free, but certainly not equal. If that wasn't enough of a strike against him, he was also illegitimate. His mother was a West Indian woman and his father a New York Irishman—and most Americans wasted little love on Irishmen in those days. While a devout Christian, he was raised in the Catholic persuasion—a third strike for up and coming politicians in the last half of the nineteenth century. His name was James O'Hara. You’d think he’d have been lucky to make clerk in the water works, but this man rose to the power levels of Congress in Washington, D.C. We know very little about him—until he moved to North Carolina in 1862. |

As an occupied town, New Bern was a haven for escaped slaves –“contraband.” Abolition-leaning missionaries and educators in the north knew that disaster awaited this new class of citizens if their minds and spirits were not educated. They came in swarms.

Not all were white: James Walker Hood, for instance, who would found the AME Zion Church and become a prominent citizen in the state, was an African American in missions; Eighteen-year-old James O’Hara also hooked up with missionaries as his means of coming into town.

Apparently well-educated, he began teaching a school for freedmen, then moved on for a time to teach in Goldsboro. There he developed an interest in law and began to study in North Carolina and Washington, D.C. As a result, in 1873, he became the first African American to be accepted by the North Carolina bar.

Long before that he was getting his feet wet in politics. It all began with a stint as engrossing clerk—whose job it was to print notices and changes regarding proclamations—to the state’s constitutional convention of 1868 and also to the state’s legislature.

The late 1800s—years racially reformed by Reconstruction rules and a new-found voting power for blacks—were fine years for a man like James to make himself heard and known. He ran for Congress in the Second Congressional District and failed. However, another African American won in his stead: John Hyman, a former slave. James bided his time—but kept himself busy. He served on the Halifax County board of commissioners for four years and, in 1875. found himself seated as part of the state constitutional convention.

An 1878 bid for Congress went down to defeat again—he lost a three-way race exacerbated by infighting within his Republican party, and by fraudulent vote counts.

He ran yet again in 1880—and lost yet again.

But the guy refused to give up. A run in 1882 finally resulted in gold. He took his congressional seat in the 48th Congress and won a second term in 1884. As congressman he was a pioneer civil rights leader, working not only for his own race’s rights, but for those of women as well. Among his attempted legislation was a civil rights amendment to the Constitution and an effort to pass a bill preventing segregation for railroad passengers. He fought for equal pay for male and female teachers and wrestled for reimbursement rights to customers of the collapsed Freedman’s Bank.

It was a worthy career. He ran for a third term—another three-way race in which another black man, whom he’d defeated in the primaries, split his vote. That race went to New Bern Democrat Furnifold Simmons, ushering in a new era in race and politics. Simmons would work to bring the Democratic Party into power by eliminating the rights of many black voters through the creation of the notorious Jim Crow laws.

Defeated, O’Hara returned to New Bern where he practiced law for the remaining years of his life. His son, Raphael, joined his practice in 1894. James died on September 15, 1905, at the fairly young age of 61. He is buried at New Bern’s Greenwood Cemetery.

This column first appeared September 15, 2008.

When I originally ran this column, I mentioned that I had no idea what an engrossing clerk was; I was soon notified by reader John R. Morgan Jr. who gave me a definition from askjeeves.com, and I explained it a couple of columns later.

1886: Furnifold Simmons The victorious run and later defeat for congress of this New Bernian helped set up Simmons' role in the Jim Crow laws.

In 1886 New Bernian Furnifold Simmons won the congressional seat for the North Carolina Second District—sometimes known as “The Black Second”—whose constituents included Craven County. He ran his race on a platform of promises that raised him above the wreckage of Republican infighting. In the powder-keg history of black-white relations in North Carolina, this congressional battle has got to be among the most curious and ironic. James Edward O’Hara, an African American, was a two-term Republican congressman hoping to win a third election in 1887. In those days, most blacks were Republicans—it had been Republicans, after all, who most strongly favored the end of slavery. In the reconstruction era, blacks had a powerful voice in elections—especially in the heavily black-populated Second District. |  Shown above, the New Bern home of Furnifold Simmons, standing on East Front Street today. Photo by Bill Hand |

But the state traditionally held its congressmen to two terms, and, besides, the party was split in 1886: O’Hara had grown unpopular with some of his constituents after newspaper articles appeared accusing him of uppity behavior with other “power” Negroes in Washington. After a bitter contest Israel B. Abbot, a black man from Craven County was able to win the Republican nod. But he did not win the hearts of most of his party: O’Hara stayed in the race, guaranteeing a split vote.

Democrat Furnifold McLendel Simmons found himself facing a cakewalk.

Say the name. Let it roll off your tongue: how can a man with a name like Furnifold McLendel Simmons not win a race in the south?

Along with having a killer name, Furnifold had a killer political instinct. He quickly began to court the black vote. “Simmons told a Craven County crowd ‘that while he was an unflinching Democrat, he was not one of the kind that set no value upon the colored man’s vote,’” according to historian Eric Anderson’s Race and Politics in North Carolina. He promised the black voters that he would meet their needs better than any other candidate—perhaps he expressed the thought that whites in Washington would have more sway than blacks—they would be better respected; they could accomplish more. The promises worked, and Simmons won at least 2,500 black votes.

He did not win a majority of total votes. But he beat out both his contenders, and that got him a ticket to Capitol Hill. He took up his duties in the Fiftieth Congress in March, 1887.

By all appearances, he did reasonably well for his black constituents, as well as for his white ones. But apparently not well enough for the “Black Second” to give him a second round: the Republican machine learned its lesson and, in the election of 1888 Henry P. Cheatham, who had been born a slave, defeated Simmons for office by 633 votes.

Perhaps Simmons’ defeat set him up for his ultimate rise to power in both state and national politics (he would eventually represent the state as senator for 30 years, overseeing a powerful committee). He certainly didn’t forget the power of the black vote for, when the state’s crumbling Democratic party appealed to him in 1898 to bring them back to power he did so by engineering a campaign of white supremacy, and by authoring the Jim Crow laws which would, for all intents and purposes, disenfranchise black voters in North Carolina for many years.

“He was not one of the kind that set no value upon the colored man’s vote”?

It was a double-edged promise indeed!

This column first appeared on March 3, 2008.

1889: Henry Cheatham

A former slave rises to represent New Bern in Congress

Henry Plummer Cheatham (1857-1935) was not a New Bernian, but he was one of a line of African Americans who represented us in Congress during the Gilded Age. (Public Domain) | Henry Plummer Cheatham (1857-1935) was born a North Carolina slave, but he rose to the ranks of Congress. Born in Vance County to a slave woman and a white father, he was emancipated in 1865 and was able to gain an education in a public school (schools for negro children were developing, mostly run by missions groups from the north, by the final year of the Civil War). Before the war, education had been illegal for blacks. After graduating from Shaw University, he worked as a school principal where he met his wife, music teacher Louisa Cherry. He must have had a great love and concern for children: in 1882 he was a key founder of the Colored Orphanage Association, helping to turn an old 20-acre farm into a safe haven for orphaned and neglected black children (the institution survives today as the Central Children’s Home of North Carolina, near Henderson).

In 1884 Henry cut his teeth on politics when he became register of deeds for Vance County. Only four years later he turned his eyes to Congress. At the time, New Bern was part of that district—sometimes called the “black |

district” because it sent so many African Americans to congress. Of recent years the representative of this, the second district, had been African Americans and Republican: John Hyman (1875-1877) and James O’Hara (1883-1887)—both New Bernians, by the way. The Republicans got into in-fighting that year; the ticket split between two blacks, and the Democrat New Bernian Furnifold Simmons was able to take his first major political seat.

Cheatham was able to take advantage of a reunited party and, with the powerful black vote, handily defeated Simmons to take his seat in 1889. As a two-term congressman, he was particularly active in social legislation for his race, backing legislation for federal education support. He also supported legislation to protect African American voting rights—ironic, since his defeated foe, Simmons, would rebuild his political career on the plank of white supremacy.

He lost his constituent voting edge in 1892 when the state redrew his congressional district boundaries, and Democrat Frederick A. Woodard took his seat (black Republicans would experience one more victory in the district, with the victory of Cheatham’s brother-in-law, George White, in 1897, before Jim Crow laws would bring the curtain down on black statesmanship for many years. Cheatham ended his years as superintendent of the orphanage he helped found.

This Column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on March 10, 2010.

1898: George H. White: Last Black Congressman

Born into slavery, George H. White would be the last African American congressman before the Jim Crow laws shut the black vote down.

George H. White. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration. | He was born on December 18, 1852 in Rosindale, North Carolina, near the Cape Fear. Born a slave, he would not be declared legally free until the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January, 1863, when he was ten years old. You might not expect much from beginnings like that but George H. White wound up representing New Bern as the last African American congressman before the Jim Crow era. He attended public schools around Lumberton after he gained his freedom. Deciding that he really enjoyed education, he took law at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He was admitted to the North Carolina bar in 1874 and took up his profession in New Bern. He also became principal of the New Bern State Normal School, which had been set up as a training institution for African American teachers. He was a Republican—Democrats were a decidedly whites-only club in those days—and under the Grand Old Party he won a seat in the state house in 1880, then the state senate in 1884. Running for office in the black-dominated 2nd Congressional District (which included New Bern), he defeated two-term incumbent Democrat Frederick A. Woodard to capture the 56th U. S. Congressional seat in 1898. It was a short but glorious term. |

Already, at home, movements were growing, partly under the guidance of another New Bern politician, Furnifold Simmons, to silence the black race in politics. This did not deter White from fighting for his people. He introduced a bill to make lynching a federal and capital crime, pointing out how it had become a weapon of terror used by whites in the south to control the black populace (in 1899 87 of 109 people lynched had been African American). The bill was easily defeated.

He also pressed for the reduction of representation in Congress for those states that denied minorities the right to vote, as called for in the Fourteenth Amendment’s second section.

North Carolina was in the process of doing just that: by the election of 1900 rules had been implemented denying the right of illiterate blacks to vote (but still preserving the rights of illiterate whites). Knowing he could not possibly carry another election he declined running for a second term, leaving the door open for Furnifold Simmons to enter his era of power.

White made a forceful final speech before Congress in January 1901, noting: "This, Mr. Chairman, is perhaps the negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress; but let me say, Phoneix-like he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised, and bleeding, but God-fearing people, faithful, industrious, loyal people—rising people of potential force.”

This column first ran December 15, 2008.