Black Men Who Owned Slaves

Some African-Americans kept their brethren in bondage... why?

Tom, a friend of mine is currently working on a documentary about the founding of James City. Recently an article about his project appeared in the S-J, prompting an interesting letter: “Please remember that New Bern and James City have a VERY RICH HISTORY OF BLACK SLAVE OWNERS. They, I believe owned more slaves than the white owners in the rest of the county. Please look into the published, but not too popular history of the true old south. Although it may not get votes it will inform the masses of the truth of New Bern!” This topic is hotly debated by activists who rarely write their commentaries without lines full of UPPER CASE SHOUTING. Our LETTER cited above is at least partially true: some blacks owned slaves. One of those slave owners did own more slaves than any white man in the county. But the other black slave owners I know of had only a few. Several African Americans in New Bern owned slaves, |  This home on New Street was owned by John Carruthers Stanly, an African-American barber, planter and former slave--who owned more slaves than the local white populace. |

which is not overly surprising since our town had a high proportion of free blacks. But James City did not exist until midway through the Civil War. It was founded for runaway slaves seeking freedom, and so I seriously doubt its residents owned slaves.

The fact that blacks owned slaves is not in question, though why they did is a hot-button topic. One view I've often heard is that blacks purchased slaves for the purpose of either freeing them (their wives and children, for instance) or to benevolently give them a better life. Carter G. Woodson was a promoter of this theory in his 1923 book Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States. It is a pretty notion, but let us view history as it was, not as what we wish it had been.

New Bern’s best-known Negro slave owner was John Caruthers Stanly, the black son of the white privateer John Wright Stanly. Born a slave, he was trained as a barber and earned his freedom. With a good business sense he speculated in real estate and eventually owned two plantations. He became wealthy and was generally accepted by the white society, so long as he convinced them that he “knew his place.” He freed his wife, Kitty, and a few others—including the barbers who worked under him, and a woman who had cared for Kitty in her dying days.

John owned more slaves than any of his white contemporaries at the height of his career: 200 is the figure usually cited, though I’ve not personally seen the official source. But he owned these slaves for the same reason that whites did: he needed their labor. The plantation South was a slave-based economy: without the relative cheapness of slave labor, it could not exist.

Those who love to crow about John's Jim-Crow leanings like to report that he was the wealthiest man in the South (or at least in North Carolina) and that no one could approach the number of slaves he owned. He may have had more slaves than any other Craven County man at one time in his career, but there were whites before and after him who owned more. New Bernian George Pollock, for instance, was reported to have 1,500.

The nineteenth century businessman and historian John D. Whitford referred to other black slave owners he knew: “Some of the free negroes were slave owners themselves, and were not slow to so traffic when their means would allow it. Too they were alway[s] rigid and, in some instances, cruel task masters. One fellow sold his own father at New Bern, the writer was personally acquainted with him, and though seemingly heartless by such an inhuman act was not vicious in disposition. Yes, sold his father to the negro speculator from Long Island, New York, John Gildersleeve, to go south in the corn fields.”

Stephen Miller, in his New Bern 50 Years Ago (written in the 1870s) mentions one Donum Mumford, a “copper-colored” bricklayer and plasterer “with slaves, a number whom he owned.” He would have hired the others from their owners—meaning that the owners, not the slaves, received the wages.

Still, if we take Mr. Miller’s words, it appears that slaves owned by blacks were the exception more than the rule. He mentioned other black business owners but only listed J. C. Stanly as another slave owner. His general view of New Bern’s colored race? “There was quite a large population of the free negro class, who lived chiefly to themselves in the outskirts of town. Some of them were industrious and inoffensive; but the greatest number… picked up a precarious living, honest or otherwise, as circumstances permitted.” Even allowing for prejudicial exaggeration that does not leave many blacks in a financial condition to purchase slaves.

You can be sure we’ll speak of the Peculiar Institution again.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on June 23, 2008.

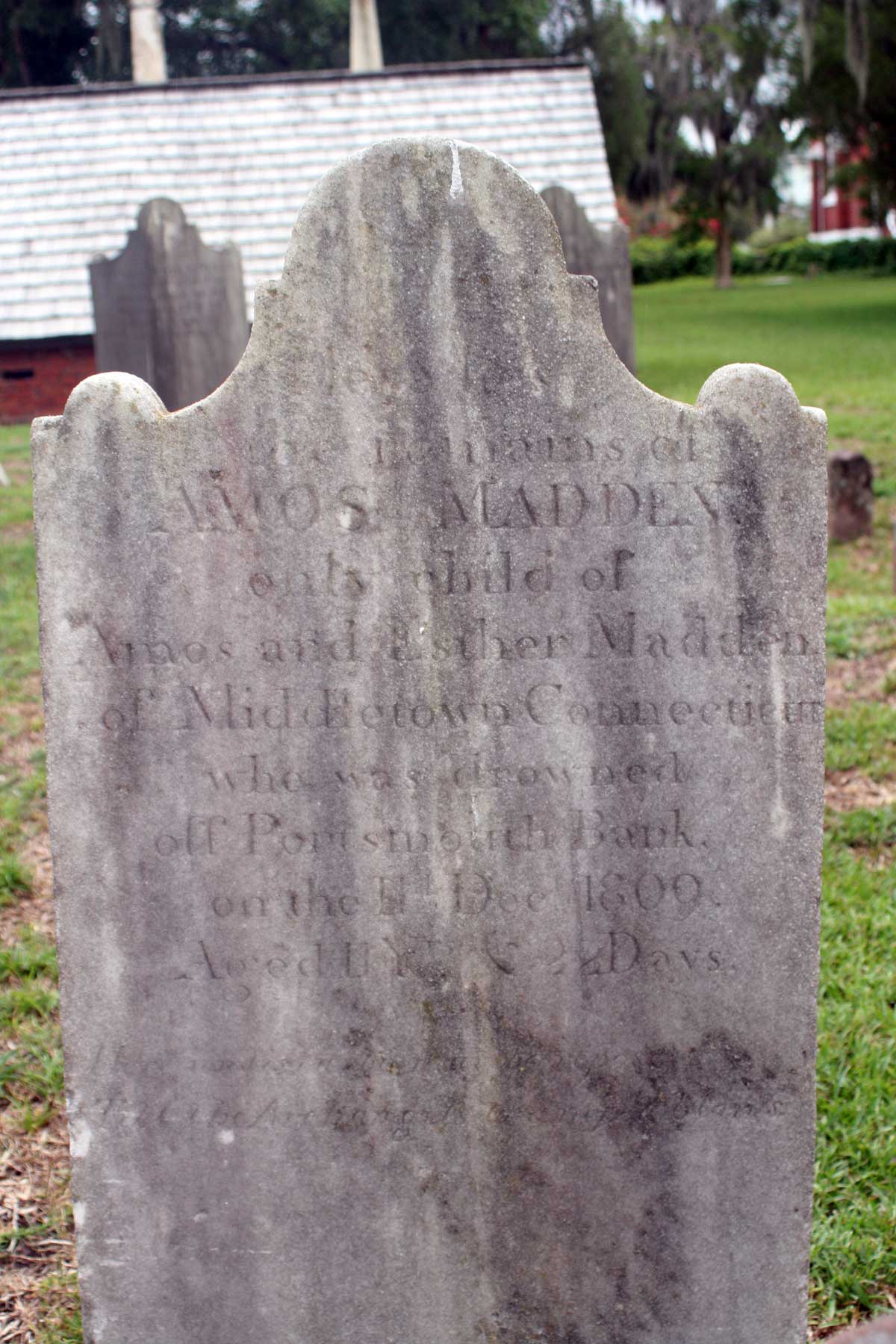

The mysterious headstone of Amos Madden, located at the Cedar Grove Cemetery, New Bern. It reads, "Here lie the remains of Amos Madden, only child of Amos and Esther Madden of Middletown Connecticut who was drowned off Portsmouth Bank on Dec 11, 1809. Aged 11 Years and 22 Days." The tombstone design, representing Heaven's gates, was popular in the 19th century. | I recently read a really interesting story that was composed on a tombstone (composed on something resting over the dedomposed... what an irony!). It offered information enticingly vague, and it has me stalking the internet, historic societies and newspapers in my attempts to flush out its dearth of details. On December 11, 1809, a boy named

Amos Madden had a very bad day: he drowned. This had to be a deeply

disturbing event for his family—even in an age when childhood death was

commonplace. Amos had celebrated his eleventh birthday less than a month before (his age, the old stone states, was 11 years and 22 days)—and now he was gone, just

two weeks before Christmas. Amos was also an only son, the

child of Amos and Esther Madden. He must have been on a trip when

the disaster occurred, for his parents’ residence was stated as Middlefield,

Connecticut. His place of drowning was “off Portsmouth Bank.” And there’s the story. So here are my questions: Where exactly is

Portsmouth Bank? We assume the waters off some coastal town. There were three

that I could locate at that time—in New Hampshire, not far from his home, for

instance. This was a town famous for boatbuilding and, having been incorporated

in 1653, was old when New Bern was born in 1710. Another coastal Portsmouth is in

Virginia, on the Elizabeth RIver. Also a shipbuilding town, it was a little

newer in 1809, having |

One last Portsmouth seems the most likely site of this boy’s death, and that is the little fishing

village and life saving station that now stands as a national park and a ghost

town on an island just south of the Outer Banks' Ocracoke Island. The town was

established in 1753, and

served as a station where the heavier, ocean-going ships transferred cargo to

lighter-weight ships that could navigate our shallow rivers and shoals. The

last resident moved out in 1971; the park service took it over in 1976. From

tourist sites I’ve read, there are a few homes and a church still

standing, and plentiful opportunity to feed the clouds of native mosquitoes.

I have not read any reference to a “Portsmouth Bank,” but being on the Outer Banks, it makes sense that Amos’s stone refers to this place.

My second question is: why was this kid buried in New Bern? I have not Mapquested the distance, but Middletown, Connecticut is far, far away, and it seems odd that—especially as an only child—his parents would have interred him clear down here. Bodies were shipped in those days, though I’m sure you wouldn’t be too anxious to have an open-coffin memorial service at the other end. If he had to be buried close to the site of his death for some reason, that still makes New Bern an odd location: Portsmouth isn’t exactly a short walk away. Why wasn’t he buried there?

A possible clue lies in the stone

standing next to Amos’s. For there, you will find, is announced the remains of

Samuel Rand, a young man of 22 who died on April 24, 1803… Samuel Rand, that

is, “of Middletown, Con.”

Why did he die? Fevers, perhaps?

Why was he buried away from home? Perhaps there was

something of a Middletown contingent in town—merchants resettled in the area,

perhaps? Perhaps Samuel was one of them—or the son of one. Could his family

have been related to Amos, perhaps through his mother?

I have tried to pursue this little

mystery—but about the only further clue I have so far is that one Amos Madden

(young Amos’s father?) appears in the obituaries in the New York Herald for September 10, 1857. I have tried to contact the historic societies of Middletown

as well, but as old as they are they apparently stare at their ringing phones,

wondering what on earth those things are… don’t even ask me about their

e-mail.

I will let you know if I discover

more of this curious tale—or if you have any thoughts or knowledge, I would

certainly love to hear from you.

Originally run August 8, 2008.

...And hear from you I did. It is odd the columns that get the most reader response—some genealogy fans with good contacts could not resist doing some digging when they read this tale. It was interesting to see where I was wrong and gratifying to see how some of my guesses were very close to correct. Mixing their findings and further investigation of my own, I was able to get a pretty complete story which I related two months later:

The last time we talked about

little Amos Madden, all we knew was that he had drowned near Ocracoke. Whether he’d fallen off a boat or slipped from a pier well before

Lassie could get help, we didn’t know.

In August I put forward the

puzzle of Amos Madden, age 11, of Middlefield, Connecticut, buried at Cedar Grove Cemetery in New Bern, drowned off “Portsmouth Bank.” Why, I asked, is he buried in

a town nowhere near these two places?

With immense help from my readers

I have unraveled quite a bit.

Though from Middlefield, the Maddens were residents of New Bern.

Mr. Rand, buried beside Amos, was also a New Bern resident. In those days, your state was as

important to you as your nationality (ever hear of the Civil War?); it would

have made sense for them to want their home turf appended to their slabs.

Little Amos had a most romantical

end. He was a passenger, alone, aboard a sailing sloop named Industry, owned by a New Bernian named Mr. Fowler. Why Amos

was a passenger we do not know—nor whether he was traveling to New Bern or to

Middlefield or where—or why his parents weren’t with him. Let us take the

Charles Dickens approach and guess that he was on a voyage to spend the

holidays with his grandparents up north.

The boat was near the little

fishing village of Portsmouth near Ocracoke. A nor’easter swept the Industry aground on a sand bar with some violence, damaging

the rudder. The crew used anchors to pull themselves free, but the damage was extensive and the boat flooded; the pumps were choked with coffee (yes, coffee) and so the

sailors found themselves bailing the boat by hand.

Mind you, the crew was probably not so addicted to their caffeine that the morning brew undid them in this way; more likely, the coffee was part of the ship’s cargo and its free-floating grounds were filling the pumps and sealing their doom.

The next day a “heavy sea” left the boat awash, and everyone climbed aboard a

long-boat, launching it and aiming for the nearest shore. It upset in turn, and everyone except

one sailor, Charles Destrow, who managed to cling to floating debris, was drowned.

Such was the end of Amos Madden.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on October 6, 2008.

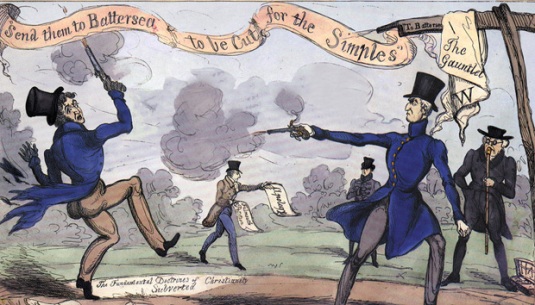

In the endless quest for honor, the Stanly brothers hunted quarry for their duels. John Stanly's slaying of Richard Dobbs Spaight is the most famous, but here is the ill-fated story of John's little brother. | In the Antebellum South, if a man was called a snake or a liar, or especially if someone tossed a bit of cake into his teacup, he was ready to take or give a life to defend his honor in a duel. Firearms were more popular than swords. This was because it evened the field: any fool can aim a pistol and squeeze the trigger. Pistols also improved your chances to survive—not even the best shooter had a very good chance of hitting his target. A smooth-bore pistol sending that ball rattling and banging down the barrel and out into the open air was no sure thing. You may as well blindfold David, hand him a snowball, spin him until he is dizzy and still expect him to fell Goliath. More often than not a shot or two was fired, and honor was declared as served. |

So while a duel could be a pretty nasty affair, and sometimes even fatal, it wasn’t the absolute harbinger of death that the movies teach us. Hollywood is wrong. Imagine that!

New Bern had a major duel—Congressman John Stanly slew ex-governor Richard Dobbs Spaight in 1802 over politics and insults. Mssrs. Hamilton and Burr made the history books with their duel, while Stanly and Spaight are lucky to find themselves nestled in some footnotes. But the Hamailton-Burr thing was a federal affair while Stanly-Spaight mainly had state-wide repercussions, so it only makes sense. Or, perhaps, Vice-president Burr had better PR men.

Actually, the Stanlys were dueling machines. They were the sons of John Wright Stanly, a Revolutionary War patriot whose privateering fleet made him rich beyond belief, and whose destiny with yellow fever made all that wealth pretty much moot. John Wright had married the beautiful daughter of a local patriot and she died about the same time he did, and of the same dreaded disease. This left the Stanly boys orphaned, without any famous parents to set moral boundaries to their heroic notions.

In the chilly month of February 1813, William Gaston, close friend of John, decided to entertain his associates by inviting them to a fine party at his home. John, at the time, was training his younger brother, 24-year-old Thomas Turner Stanly in the art of lawyerhood, and so the youth was invited along.

Also at the party was Louis D. Henry, the young apprentice of the prominent attorney Edward Graham. Louis and Thomas knew one another. Typical youths, they tended to joke and sport with each other. Apparently, also like typical youths, they were girl-crazy, and there at the party was the lovely young Lucy Hawkins of Warren County.

One silly girl, two hot-tempered young men, one party (complete with cake) = one dead Thomas. Let’s see how it all came down:

Thomas, in a jovial mood, winged a bit of cake at Louis. It landed in his tea cup, splashing his vest. Lucy looked at Louis and, laughing, asked, “Are you going to stand for that?”

Testosterone took center stage.

Before you knew it, Louis had challenged Stanly to a duel. Thomas sought the advice of his brother on the matter. John replied that accepting the challenge would be a very fine thing. Thomas probably saw it as a chance to match his brother’s reputation.

A day was set – Sunday, on Valentine’s Day, ironically enough. North Carolina had outlawed duels, since brother John Stanly had proved them to be so costly in terms of ex-governors. To sidestep these laws, Louis and Thomas crossed into Virginia via Gates County, putting the scene of their fight just southwest of Norfolk, probably near Chesapeake and very likely somewhere along the Dismal Swamp where a canal provided easy transportation. We don't know if Lucy was there. For his second, Thomas brought George Badger, a man who would develop quite a reputation and name for himself, later on. A Dr. Boyd was Louis's second and another physician, Dr. Scott, came along as seconds.

Duels were fought in ordered rounds: the duelists drank a toast, lined up back to back and marched their paces. They turned, and on a given order, fired--or took turns firing. If the first shot missed—and more often than not, it did—the seconds would see if "honor had been served," or whether apologies would be given to end the duel. If not, they fired again and repeated the steps until the duelists gave it up or someone got wounded or killed. On rare occasion things would really heat up and the seconds would start banging it out as well. Most often, the first shots were enough; indeed, sometimes the men purposely fired into the air, and it all turned out to be a dramatic sham in the name of honor.

Such was not often the case with the Stanlys. A duel was a duel, and someone was supposed to die. Louis and Thomas made their paces, turned and fired. Somehow Louis beat the odds: his first shot buried itself in Thomas's right side, piercing his heart, and the younger Stanly dropped dead on the spot. The victor fled to New York but later returned to North Carolina, where he pursued a successful, and even brilliant, political career. He died in 1846 and was buried in Raleigh.

You’d think Thomas’s death would have cooled the Stanly blood, but it did not: another brother, Richard, dueled with swords in the West Indies and was slain. Even John Stanly’s son Edward, according to Miller, tried his hand—against Alabama Congressman Samuel W. Ingle. Edward's second, interestingly enough, was Jefferson Davis. He and Ingle both missed on the first shot—and had enough sense to stop.

Wonder if it had anything to do with cake?

1825: Charlie Roach

Every town's gotta have it's black sheep. Meet Charlie...

I wanna talk about Charlie Roach. It’s a name so decadently

descriptive you’d swear it was invented by Charlie Dickens for an Oliver Twist sequel. He’s described in a delightful

little historical book titled Recollections of Newbern Fifty Years Ago, written in 1874 by Stephen F. Miller. The author had

been a law clerk in New Bern around 1822 and filled this brief tome with a

number of entertaining characters from the well-known to the seriously unknown of his past, including our own Charles Roach. Charlie was “by far the most skillful artisan in

town,” Miller thought. “”There was nothing in the most delicate machinery which

his genius could not accomplish.” He had a “head and physiognomy of striking

case, very much resembling the busts of Shakespeare.” This noble visage

contained a mind that was equal parts of Jeckyll and Hyde. “His name was

coupled with infamy,” Miller wrote, “an object of terror to all who were

acquainted with his character and exploits; yet in his ordinary deportment he

appeared to be the gentlest and most inoffensive of all human beings, while his

large black eyes glistened like diamonds, and the expression of his mouth

indicated the pleasure which he felt in mysteriously annoying men beyond

redress.” He had more than a passing acquaintance

with the interior of the county jail, having been caught a few times as a fence

receiving stolen goods. He’d also been jailed for doing |  Make this guy about 250 years younger and remove the funky collar and you might be looking at Charlie Roach... |

business with slaves—very possibly escaped slaves who often survived by trading begged or stolen goods for coin or food.

He had an especial talent with

repairing books and, apparently, in playing with locks. Miller noted his

fondness of picking the locks of the bank at night and leaving all the doors

open. He did not steal anything—in fact, he guarded the place by going inside

and waiting, grinning, for the flummoxed police to arrive. I imagine him greeting them, “Good morning,

gentlemen, so fair and foul a day I have not seen…!” From the background enter the Three Weird Bank Tellers...

He was also a talented landscape

artist, capable of copying any object from nature. One hopes he was not also

talented at copying legitimate legal tender. “Had better principles influenced

his life [then think what] marvelous faculties might have been achieved for

mankind,” Miller imagined.

Yes, but what a colorful character we might

have lost from our past!

This column first ran December 8, 2008.

1829: The invention of the 14-shooter

Some believe that Sam Colt's patented revolving-chamber was stolen from a New Bern inventor.

A popular advertising slogan of the 19th century said: “God made men. Samuel Colt made men equal.” This Connecticut Yankee in King Lincoln’s Court sold more handguns for the Civil War than anyone else. New Bernians love to claim everything as having happened here, first, but seeing that Mr. Colt was a Yankee tried and true pretty much steals the honor of the revolving gun invention from us, doesn’t it? Well. Not necessarily. Enter John Gill, a New Bernian with hugely bad luck. A man of many talents, he was a locksmith, watch-maker, goldsmith and silversmith (Tryon Palace houses some of his work). According to the US Patent office, John in 1829 (or in 1820, if we are to believe our own historian John D. Whitford) invented a revolving-chamber gun. It was far more ambitious—or perhaps cumbersome is the word I’m looking for—than Colt’s would be, for it had 14 chambers. Whitford remembered seeing and handling the gun, prior to the Civil War. Despite his many talents, John was not a man of money and his friends advised him not to waste his funds on a patent; nonetheless he intended to protect his invention. A few years later, around 1836, he went by boat (trains from New Bern were a dream of the future then) to Baltimore, but before he could finish his trip to D.C., he got violently ill. |  Connecticut Yankee in King Lincoln's court: Sam Colt was declared the inventor of the gun that made him famous. But a New Bern inventor had the same idea--and some suggest the Northerner stole the idea and beat him to the patent. |

While recovering a friend convinced him to let him borrow the weapon. We don’t know what happened during that time, but when Gill finally got well enough to knock on the patent office door, he found Samuel Colt had beat him to the punch with a patent for his own six-shooter.

Gill was convinced that, somehow during his illness, Colt had gotten hold of his design and stolen it. Whitford himself declares this alleged theft as fact: “John Gill [was] the inventor, it is claimed and justly it is believed, of what is known as Colts revolving gun. Out of the credit and profit of the invention Gill was tricked while visiting Washington to obtain the patent. “

Gill kept that gun for many years and showed it to Whitford, who remembered seeing it on many occasions before. After his death it was passed on to the Matthews family who kept it until the Civil War. When that war broke out marauding Yankees came upon it: exit one historic artifact from Newbern-town.

No wonder some natives only refer to Yankees with the prefix "Damned"!

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on June 15, 2009.

1830: Antebellum dog laws And you think today's dog laws are tough?

New Bern has a curious history with animals, some of it pretty dark. Take Mary Oliver, last resident of the Attmore-Oliver House (now a museum with the Historic Society—the house, not Mary). According to Ghost Stories of Old New Bern, she hired a man to kill the cats living on her property then refused to pay him. For revenge he buried the cats with their heads above the ground. (her ghost, we’re assured, still stomps about the house in anger). True or false? The ghost is too busy stalking to say and I’ve not heard of any archeological digs for cat bones. The book has another animal cruelty tale about an unknown (but claimed by some to be one McMurdy) dog warden who used to club dogs that weren’t on a leash. When folks walk their dogs at night their pets get strangely annoyed by phantom dogs that race about. I can’t vouch for the phantom dogs, but the rest of the story is pretty close to true. Dogs were allowed to run loose. So were cattle, pigs and goats. It’s why they walled Cedar Grove Cemetery in. The New Bern Progress in 1861 reported that “A fine Cow was seized on East front street yesterday by a large unruly bull dog and dragged into the river and very narrowly escaped being drowned. Wouldn’t it be better to kill dogs or keep them up?” –one of the earliest editorials for leash laws that I know. |  I read this column to my dog, Sabre, and this was pretty much her response... |

Stephen F. Miller, in his New Bern 50 Years Ago, reminisced about people he knew when he was a young lawyer’s apprentice here in the 1820s. He recalled James A. McMain, a merchant who also served as town constable. There was no leash law at the time, but there was a licensing law: If you owned a dog it was your responsibility to purchase a collar from the city treasurer. Any dog caught without it was punished with quick death from the constable’s club. “I have seen many fine dogs, from Newfoundland to the common Spaniel perish under the club of the constable as with his strong left hand he inflicted the penalty of the law in open market and elsewhere,” Miller recalled.

If you’re walking your dog tonight and phantom wieners run by, see if you can glance McMain’s ghost and fling a rock at him for me.

1836: Athens of the North Carolina

New Bern has always had a proud theatrical heritage.

A team of more modern thespians with Athens of the South Productions perform a comic murder play in 2008. | In its earliest days, New Bern was the “Athens of the North Carolina.” Colonial Governor William Tryon, in a letter to the Bishop of London, mentioned a troupe of actors under one Henry Giffard. Tryon hosted a circus, too. Okay, the “circus” was really the general assembly, but we’re talking semantics, here. New Bernian James Iredell

witnessed an apparently “execrable” performance of Moliere’s The Miser in 1787, according to Alan D. Watson’s history, and

in the 1790s Thomas Turner’s distillery on East Front Street served as a

theater, complete with a Negro’s gallery. From its earliest days, St. John’s

Masonic Theater has been a center of stage and |

theater. It is still used that way—one of the oldest operating theaters in the country.

Nineteenth century New Bernian Stephen W. Miller fondly recalled “Mr. Herbert’s Theatrical company of 1823”:

“Mr. Herbert played Richard III, and was quite successful in genteel comedy in the character of an old man… Mr. Drummond was most effective in gay scenes, representing fast young men… In Goldsmith’s admired comedy, “She Stoops to Conquer,” Mrs. Waring made a brilliant display as widow Cheerly.” One Thomas Pasteur was so intrigued by her performances that he followed her to Charleston, never to find his way home again.

Miller also recalled Alexander F. Gaston who “sustained a character in knee-breeches. Persons who have seen the figure of that gentleman, stooped in the shoulders, yet six feet and four inches high and his knees bent inward, can well imagine the comic effect he produced on the audience. It was the climax of the entertainment. “

A New Bern Spectator article of September 5, 1834, mentions performances by visiting actors from Philadelphia, Baltimore and Petersburg—august presences who made “Mr. Conner’s company… decidedly superior to any that has performed her for several years.”

Coming into the Civil War a healthy theater season was run by a Mr. Bailey who rented out the Masonic Theater for a two month season. His most notable presentation: "Our American Cousin" by Tom Taylor--that infamous comedy that witnessed President Lincoln's assassination in 1865.

The town's most prominent theater, the Athens, was built in 1911. Prominent, but not only: The masonic hall is still used, and plays can be regularly seen at the Shriner's building while the Chelsea Restaurant is a frequent site of dinner theater. At least four companies are active, including the Civic Theatre (operating out of the Athens), Rivertowne Repertory Players (at the Shriners), and a couple of "indy" companies, PPS Productions and Athens of the South Productions.

This column first ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on December 3, 2007.

1854: Captain Roberts' Spider Lilies

They're native to Japan, but in America New Bern had them first.

This week we celebrate the birthday of Captain William Roberts. If you’ve never heard of him, then you’re apparently no connoisseur of flowers.

While he did a number of things that should give any local man immortality—fought as a Confederate sailor, worked with Commodore Perry in the fleet that opened Japan to trade with the world—it is a humble lily for which we remember him.

He was born February 17, 1822—where I do not know, but he wound up living in New Bern. He married Elizabeth McKinlay Roberts, five years his junior, which was about average for the day.

She was a sailor’s wife—meaning she went months and probably years without seeing him. Roberts joined the United States Navy in 1839 and served with it until 1860, when a minor argument between northern and southern states split the country and killed off half a million men. Commodore Matthew Perry’s fleet sailed to Japan in 1852 and, again, in 1854. Japan was a land veiled in secrecy and obsessed with keeping foreigners off her soil. But Perry, a man with a most constipated expression (that even Japanese woodcuts captured) was a man with a fleet of big, black, smoke-belching ships that could reduce Japanese towns to toothpicks. He got his trade agreement and—perhaps—the Japanese got a simmering humiliation they would not live down until they avenged themselves on December 7, 1941.

When Captain Roberts returned home, he presented Elizabeth with three dried-up flower bulbs which she planted. They were Lycoris radiata—spider lilies, a most interesting, unusual little flower that blooms from late fall through early winter. But Elizabeth’s lilies didn’t. They sat under the ground, apparently sulking, for several years. It wasn’t until the Civil War began that they finally popped up out of the ground in all their glory. I have read that these bulbs, planted in spring or summer, take care of themselves, making them my kind of flowers.

Roberts possibly served on the CSS McRae in the Gulf during the Civil War—at least a William Roberts shows up on the crew’s roster. The McRae sank on April 28, 1862, after limping into harbor following a fierce battle with Unon gunboats four days earlier.

Roberts is buried in Cedar Grove Cemeter where his spider lilies grow wild in his honor.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on February 16, 2009.

1855: The Gaston House

New Bern's finest hotel opens for business.

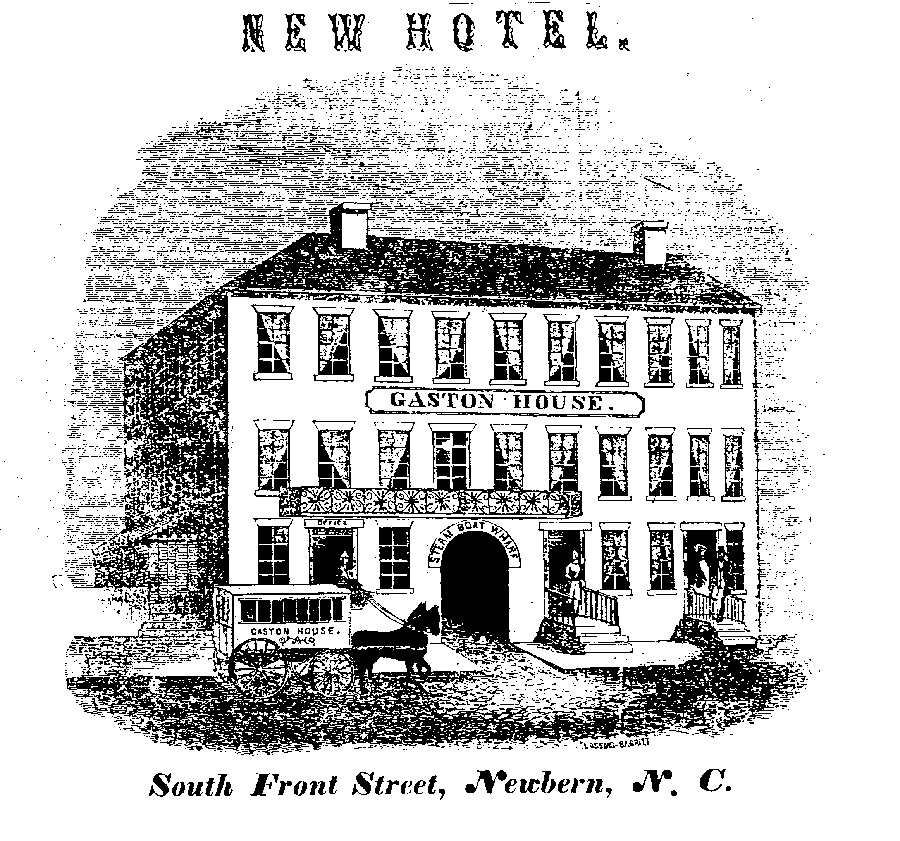

This illustration is from the original advertisement of the Gaston House opening in 1855. | A lot of important stuff happened in 1855—or was about to. In engineering, the London became the first train in the world to cross a

suspension bridge—it spanned the river near Niagara Falls and was designed by

John A. Roebling, who would later design the Brooklyn Bridge In literature, Thomas Bullfinch

finished his Bullfinch’s Mythology, much

to the delight of scholars and the abhorrence of their students. Whitman’s Leaves

of Grass hit the streets, a poetic

masterpiece that would be a commercial failure. In his musty Cambridge

dwelling, in his study in the twilight, Henry Wadsworth, called Longfellow,

wrote the poem Hiawatha. The hot dog was three years old (no evidence it had made it to New Bern yet). Commodore Perry’s trade agreement with Japan had been signed for a year. Missourians had just flooded Kansas, illegally voting a pro-slavery legislature into that wannabe-state. |

Elevators were two years down the road, and Isaac Singer was even now eyeing that wondrous sewing machine invention of Elias Howe’s, envisioning it being manufactured for the masses.

Meanwhile, on April 23rd in New

Bern, the Gaston House hotel was opening for business.

We are not talking a small potato in the historical

sack here. The Gaston (named for a prominent judge and congressman, not a

stomach condition) would become known as one of the finest hotels in the South.

Proprietor T. L. Hall was

enthusiastic in an announcement that ran in the Newbern Journal on April 15, 1855:

“…As the entire House is finished and furnished in a superior style, with everything new, adapted to the comfort and convenience of guests, the Proprietor feels that he can give entire satisfaction to everyone who may favor him with their patronage.

“As to the Table… our almost daily communication with New York will enable it to get its supplies from the North, as well as from our home markets.”

That access to northern cuisine would probably be a

big boon to the Yankees who would claim the place during the Civil War.

During that war, the hotel

underwent its first name change: “The Union Hotel was formerly the Gaston

House,” Unionist John Hedrick wrote from there in a letter to his brother in

1862, “as the old sign over the door, which has been imperfectly covered by the

paint of the new one, indicates.”

In 1870 Samuel Rogers Street, Jr,

who would build a fine, still-standing home on Pollock Street in 1882, owned

it.

By the turn of the century, when

lumber baron James Blades manned its helm, the business had gone back to its

old moniker of “Gaston Hotel.” A 1910 publication, Souvenir of New Bern,

North Carolina, described it as “the best

hotel in the state,” noting that it had recently undergone a $100,000

renovation. That would be a chunk of money in today’s dollars.

The publication went on to claim

that it featured sixty sleeping rooms from a commodious 14x18 feet to an

enormous 35x50 feet. Hot and cold water, electric lights, private bathrooms

with porcelain tubs, steam heat—and in a bit of PR that reflects today’s

standards, these rooms were “not excelled in their sanitary qualities, this

being one of the particular points of the management to look after.”

No roaches here. If there were

any, they were clean.

The kitchen, the advertisements

bragged, “is supplied with the latest improved cooking appliances, bake ovens

and steam tables.” “The promptest service” is guaranteed.

Photographs of the period show

some fine rooms and dining rooms; polished spittoons are strategically placed

to keep the tile clean.

If you wish to tour the hotel, you

may stroll down South Front Street’s southern side, between Craven and Middle

Streets. Turn up your imagination, though: the old edifice burned to the ground

in 1965. Only its grandiloquent ghosts remain to greet you.

The hotel does have one curious

descendant still standing, however—Mr. Street’s old Pollock Street digs have

been transformed into the Aerie Bed and Breakfast. It’s nice to see things

following in the family line.

This column originally appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on April 21, 2008.

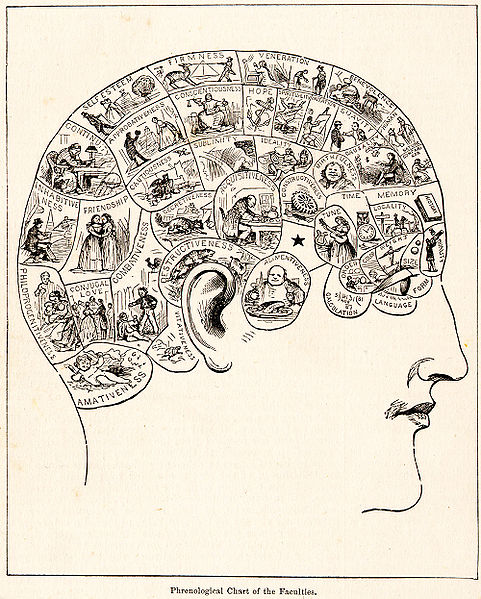

1861: Phrenology

Regions of the Mind-—Phrenologists put the "quack" in 19th century medicine... This chart shows the supposed character traits each part of the skull describes. | Step right up: the good doctor will be with you shortly. Welcome to the lovely Gaston Hotel, by the way—The

finest in the South this summer day of 1861. Everyone comes here to set up

business and enjoy the kitchen’s fine cuisine. I’m sure you noticed Lieutenant

Cone down there in the lobby, signing up the boys for the army—open season on

Black Republicans you know! Sit down here and uncover your head. Dr. McMullen will be along shortly. And, uh, if you hear a sudden thump or a bang, or an “Ow!—Gosh darn it!” or even worse muttered under his breath, don’t pay no mind. Dr. McMullen is blind. Blind as a bat—no, blinder than that. Blind as a brickbat. But phrenology, you know, goes by feel. Reading your head’s like reading—whaddyacallit?—Braille! You’ll feel like you’re getting a

massage. His fingers just dance here and there, feeling the little bumps and

dents in your skull. When he’s done he’ll tell you more about yourself than you

ever knew. He read my head just

yesterday and said I have an intellect the size of a county. I was real curious

about the science so he explained it to me. See, this phrenology stuff was started around 1800 by one of them German doctors, Franz Gall, and today it's |

all the rage, North and South. See, phrenologists believe that your brain is the organ of all those propensities—I think that was the word. Different spots develop different traits. Like, right here I think—where I’m tapping—that spot determines your argumentativeness. The bigger that spot is, the more you like to fight. And if the spot is really small, then you have the passion of a mouse. If the spot’s big, well, that’s because the skull’s got to have a bump to contain it; if its really small, it has a sort of ditch—I think the doc called it a fissure—because there’s just a hole where that trait should be.

Now, Emmit over at the Dry Goods Emporium thinks it's so much hooey, but I'll bet Emmit's got an ignorance-bump the size of a potato. But you just trust ol' Doc McMullen. Like that ad in the Daily Progress says, his being blind just makes his readings that much more interesting!

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on March 2, 2009.