It was the American philosopher George Santayana who said it – “A country without a memory is a country of madmen.”

And then there was Oscar Wilde who noted, “Any fool can make history, but it takes a genius to write it.” I ask you: what better reason is there to start up a history column than as a preventative to community madness, and so that I can walk around feeling really smart?

New Bern is awash with history. Ours began before that funky Swiss guy in the flowing wig stepped ashore in 1710, and it didn’t stop happening after boys in Union Blue took us over in that “War of the Northern Aggression” – the Civil War.

Here are just a few of the tarry footprints we’ve left behind:

• Indian village, pre-1710.

• First colonial capital and site of the first printing press in North Carolina.

• The birthplace of Pepsi.

• Home of the man who invented the land mine and—some will argue, home of the guy who really invented the gatling gun and the revolver pistol.

• Here was the residence of the last African American congressman before his race was banished from those halls by the Jim Crow laws of the turn of the Twentieth century.

• The biggest fire in North Carolina history.

And don’t forget that Blackbeard never came here, though we really wish he had.

Duels, hangings, revolutionary intrigue – you name it, we’ve had it. Holy men and scoundrels, statesmen and politicians, happy events and tragedies. As a community layered in historic houses and littered with historic markers, we could almost say we are our past.

“Know thyself,” Aristotle said (which is remarkable, since English didn’t exist then). Like a child lost on a residential street, it is rather sad to have no idea where you’ve come from—hence giving you no real clue to where you are. This happened to me once; an elderly fellow discovered me, gave me cookies and with some patient questions found out who I was. As a result, he was also able to help me find my way home. Now, you will have to get your own cookies, but I’ll be glad to meet you each Monday and chat a bit about the coastal roots that tell us who we are or, if you are new to the area, who you are about to be.

Oscar Wilde’s amazing prophecy about my brilliance aside, I realize there are residents with far deeper knowledge than mine. If you have any comments on this column, or ideas of on subjects for a future one, I encourage you to send me a line.

Bill Hand is author of Remembering Craven County: Tales of Tarheel History and A Walking Guide to North Carolina’s Historic New Bern, both by History Press. The books are available at many local stores and Walden’s.

This column originally ran on November 19, 2007.

If he’d followed the tradition of naming

everything after the Indians he’d run out, you’d be reading the history of

Chatokka now. But, instead, our city’s father was bound to honor his

mountainous homeland and called this not-so-mountainous spot (elevation: 10

feet) New Bern, instead.

|  Though named after the Swiss city, the "Bern" in New Bern means "Bear." It's a symbol you're not likely to miss in a stroll downtown, from the bear over the Chamber of Commerce sign (at left), the one sticking out of City Hall (below) the guy emblazoned on our police cars (above) or in the form of concrete or wooden sculptures about town (not pictured--but take a stroll and have a look. Really. You need the exercise. Now that you know what "Bern" really means, let's have a read at how it's really spelled...  |

Early on the single-word moniker of “Newbern” was king. Others wrote “Newberne,” with that silent “e” at the end. The effect was more intellectual than verbal: Say it, and you’ll hold your pinky up as you sip your morning’s Earl Gray.

James Davis’s original publication put it as one word, sans the “E.” Our founding fathers, whose records and letters are so carefully preserved in the Colonial Records, spelled it every way imaginable – one word, two words, with a silent “E” and without. Even North Carolina’s most capable colonial governor, William Tryon, spelled it as both one and two words.

The Virginia newspapers preferred one word, and so did Mark Twain, who wrote a delightful and true story about a freed slave woman’s experiences in our town during the Civil War entitled – are you ready? – “A True Story.” George Washington showed some creativity in his journal when, on April 20, 1791, he managed to spell it two different ways in two consecutive sentences: “Newbern” at first, then “Newburn,” as though the town were a fresh and hot topic.

The Yankees who controlled our town during the Civil War also preferred the single-word name. Most soldiers’ letters’ return addresses carry “Newbern,” as do many of the period’s maps. An 1862 map, meanwhile, describes the “Battle of Newberne” (such high-falutin’ cartography must have been the work of a Bostonian).

It was not until 1897 that someone finally got around to settling the city’s spelling in the law books. Ignoring the popularity of the single-word name (yes, they actually had the audacity to go against Mark Twain), the final spelling split the word and dropped the “E.” We are New Bern to this day and for the foreseeable future.

Like the constant shifts in her spelling, New Bern’s personality has been ever-changing: sleepy fishing village, war-torn settlement, maritime center and colonial capital, occupied military center-of-operations. The twentieth century saw her turn from a major lumber center to a sleepy, decaying southern town and awakening at last, yawning, to the benefits of her history for financial and cultural capital. As you can see, it leaves us plenty of fodder for meeting in this space again.

This column first appeared January 14, 2008.

That's me, stomping about the muck near Mattamuskeet in March of '08. Not sure what the hula thing is with the hands... I must have either thought it would attract swans or repel cottonmouths... | Last week was my 52nd

history column for the Sun-Journal—a

solid year. You’d think I’d be running dry on topics but, glancing over my

notes, I see plenty more to go. If

facts run low, I can always turn to revisionism: Did you know that New Bern was

invented by Al Gore?

I love language and I love history: this has been a double affair. I started with a few subjects I knew, and adapted a couple here and there (especially at deadline crunch times) from the couple of books I’ve put out. At other times I’ve dug more deeply into things I knew only vaguely—and in that process I’ve often stumbled upon interesting quirks and trivia that would make new columns. Some ideas have come from readers and colleagues; I’ve plumbed local history books, historical records and, once a book on European culture and |

I’ve emphasized people over

specific events. People are endlessly fascinating, after all. Dry facts bore

me—or sometimes I become obsessive with them. I wind up with lists and charts

so convoluted that it would make even a nerd scream. Too many factoids can make

Billy a dull boy.

I’ll admit to ego: a couple of times I’ve been

recognized from the picture that runs with this column; if it happens much more

often I’ll have to buy a larger-size stupid hat.

E-mail me: what do you read about?

What New Bern events do you find most important? (I’d love to do a series on

what local historians feel are the five most important events in our past).

Would you like some stories about particular houses and businesses in town?

Something I have yet to touch?

I am breaking from the past this week to give you a short note of thanks. I’ve appreciated the comments and e-mails, the letters and phone calls. The editors at the paper and my proof-reading wife, Roberta, have been great, too. Two-thirds of what I’ve written about was virtually unknown by me a year ago, so I especially thank you for driving me to grow and learn.

This column originally ran December 1, 2008.

Nicknames of North Carolina

Welcome to another round of historic wisdom about New Bern, North Cackalacky. Today, we look at

nicknames. New Bern sometimes refers

to herself as the “Athens of the South.” This is an old, somewhat altered

phrase from antebellum days. Athens—in Greece—was known for art and grace, and

so New Bern. In my hours of research I have never seen “Athens of the South”

come up—but the more humble phrase “Athens of North Carolina” comes up

frequently. Still, humble or not, “Athens of the South” slides better off the

tongue. Let’s keep it. North Carolina, of course, has its nicknames. You can't join the union if you don't have a nickname. Russia tried to join the union back in the 1800s, but they were too uptight to come up with a name and we rejected them. The chairman of the union-joining committee, Karl Marx, was quite upset. He tried to buy some rope with us, and the rest is history. Okay. Maybe not. |  |

But we do have nicknames—more than our share, from the serious to the nonsensical. For instance, I have seen us referred to as the "Tobacco: It's a Vegetable" state.

Here are a few that are a little more "official":

Old North State. This goes back to 1712 when Carolina was first

divided into North and South. Why someone decided we were the old

half I don’t know, but it makes me want

to sit in a rocker. This is also the title of our state song, by the way.

Turpentine State. We used to churn out a lot of turpentine. Duh.

Tarheel State. This may simply be an old reference to North Carolina's penchant for naval stores, but legend and some evidence give it a romantic Civil War source. One story states

that a Carolina regiment and another regiment got caught in a hot battle: the

other regiment fled while the Carolinians held their ground. The soldiers later

said Carolina tar would have to be applied to the others’ heels so, next time,

they would stick to the battle. I’ve seen another source stating it was the

Carolina regiment that fled.

Historian R. B. Creecy pushed the first version and I’m sure his being a

Carolinian himself didn’t give him any bias, so he must be right.

Cackalacky. Apparently military types like to use this name.

The term goes back to the 1800s. It is possibly tied to a condiment of the same

name, made, I believe, from a sweet potato base.

Rip Van Winkle State. Here is a truly bucolic and insulting title. One

promotional website hopefully guessed it referred to our Appalachians, which

resemble the Rip’s Catskills Mountains home (lots of dirt, rocks and trees; higher

elevation than New Bern: Yep, they look a lot alike). However, it was a name

other states gave us because they claimed we Cackalackys were snoozing while

America grew up around us. In antebellum days this was at least partially true.

Variety Vacationland. If this sounds like a promotional brochure, you’re

right. An attempt to improve tourism, the Division of Advertising came up with

it in 1937.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on December 12, 2009.

Researchers beware!

An encampment at the reconstructed Tryon Palace. Beware where you find your information on the original governor here! | A note to the casual researcher out there: be careful what websites you trust for facts. And treat Wikipedia like historical fiction: Interesting and informative, but don’t trust the details. Consider its entry

on William Tryon. It is useful to read—there’s a fair amount of detail on his

life. Whoever wrote it (the authors are anonymous and can be anyone) knew a lot

of stuff. Unfortunately, he thought he knew a lot more than he actually did. Some errors were

minor, and it could be that I am just being picky: the article reported that

Tryon’s father-in-law, governor of Bombay, had died in Cape Town on his way

home from India. More exactly, he died on board the |

ship, somewhere off the southern tip of the Dark Continent, and was buried in Cape Town.

Tryon arrived in

America, the article states, on October 9; but Tryon himself, in a letter to

the Earl of Halifax, reported his arrival as “Wednesday the 10th.”

The article’s date source was a book on North Carolina architecture; mine,

Tryon’s correspondence. After the death of his predecessor, the article states,

The article is

dangerously vague at times: it goes into moderate detail about Tryon’s raising

“an elaborate governor’s mansion”: the authorization of the legislature for

raising funds, the use of Philadelphia laborers, the years of construction. Sounds

like quite an act of ego, one might think – especially since the article never

mentions that the mansion’s purpose was also that of a “government house” (the

words Tryon used to describe it) in which important records could be kept and

governmental business would be conducted.

There are other

errors, but the largest is a concluding statement that claims: “Many

descendents of William Tryon reside in Connecticut, and upstate New York.” Very

curious, as Tryon has, so far as we know, no direct descendants. Although he

fathered a love child, the daughter that resulted from his marriage, Margaret

Tryon, died childless—in an accident while eloping. His son died as an infant.

I have found

maddening errors in other articles about local figures in the Wikiworld of

almost knowledge.

If you are going

for facts, try to find biographical sites run by reliable

institutions—colleges, state historic sites (not tourism or community welcome sites), libraries, museums, and so on.

Don’t be Wiki-lazy; there are a lot of good sites for people willing to do a

little honest digging.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on May 4, 2009.

ADDENDUM: This particular column has stirred up a number of letters from the current batch of Tryons living in America--at least one quite angry that I would suggest he was not a direct descendant of the governor. I will admit he could very well have direct descendants through Mary Stanton--but those descendants almost certainly would not carry the name of Tryon. Also, Tryon was one child of a fairly large family and, or course, there would be descendants from his siblings--but it is highly doubtful that Tryons today are directly descended to the governor himself.

There are a couple of other William Tryons, however, who were not the governor. For instance, there was a William Tryon (1635-1711) who lived in Connecticut prior to 1663 with his bride Mary Steele. There is also the painter, Dwight William Tryon (yes, it is ironic that the link is to Wikipedia!) (1849-1925). Perhaps some of the current Tryons are descended from these?

I will also note a French gentleman who wrote to me, pointing out that even the most "legitimate" sites, sponsored by historical organizations and museums, can be erroneous. He referred in particular to the Te Papa museum ("a local equivalent of the Smithsonian Institution," he noted) which made the "terrible error" of reporting that in France "kiwifruit" is sometimes referred to as a "vegetable mouse." One can be sure the culinary French would never do such a thing--at least not until "Ratatouille" makes more inroads in the kitchens of the land.

A final note: Since this column first appeared, Wikipedia has updated its entry on William Tryon, correcting its errors.

What If...?

Maybe it’s all in how the cards play out. During the Civil War, New Bern was—comparatively speaking—a pretty big town. Smaller only than Wilmington, she was more than twice the size of Charlotte. Even Atlanta, which war and Margaret Mitchell would enshrine in romance and tragedy, was only a little more than twice our size at 9,554. But look at us now. We (27.650) have just over five percent of Atlanta’s population (537,958); only about four percent of Charlotte’s (716,874). How did they get so big? Why did we stay so small? There are probably hundreds of little reasons. But history can hinge on singular events. Take Lincoln's assassination; take Waterloo. |  Some New Bern crab cages. We are a town of crabs and tourists (not always easy to tell apart). But could a few historical changes have made us something very different? |

Do you ever wonder—I speak to you historical types—what New Bern might be today if certain events had gone another way?

Here are three candidates:

• 1788: New

Bern remains the capital of North Carolina. Ruffians across the state are

pressing hard to move the capital inland, toward a location more central to the

population. However, moneyed influences along the coast and infighting among

those who wish to land a capital in their county work together to defeat any

such bill: New Bern remains the center of government in this state.

• 1905: Two

years after the appearance of the second “Buggymobile,” local entrepreneur and

carriage maker Gilbert Waters convinces North Carolina industrialists to raise

the money to build a factory in New Bern. By 1907 Buggymobiles are rolling off

the assembly line.

• 1923: Caleb

Bradham is able to shore up his popular soft drink empire with business loans

and investments. Though teetering on the brink of bankruptcy over sugar prices,

Pepsi-Cola survives in New Bern while smart marketing assures that the city

will forever be its corporate home.

There are other events that, I think, might have altered our history in significant, though less dramatic ways: what if enough extra troops had poured in early in March, 1862, giving enough men to properly man the lines at Fort Thompson? If the South had won the Battle of New Bern, and the city's defenses had been continued to be improved, what effect (if any) would it have had on the war? Could the town have held up as long as Wilmington? Would the extra port of entry had any real effect on supplies to the starving South?

...Or, what of the Fire of 1922, which burned down almost the entire black section of the city? As a result, many African Americans emigrated to other states (many to Ohio). A resulting change was that New Bern's demographics changed from a city whose population was mostly black to one that was mostly white. Wind, a lack of equipment and firemen (most of whom were in Raleigh watching a championship high school football game), and a "red herring" fire at a lumberyard on the riverbank conspired to allow a little chimney fire to take out one-fourth of the town. What if that chimney had not caught fire at all? Or if the firemen had been able to respond more quickly?

There you have it: history-altering events in New Bern… but would they be history-altering enough? What if we were the capital of Pepsi—or if we were a “Little Detroit”? What if, in 2009, Tryon Palace—not the rebuilt one but the original building (for, as the government house, events wouldn’t have conspired to burn it down) were the governor’s mansion instead of a tourist spot? Would we be a city of skyscrapers, museums and industries? If so, would that have been a bad thing, or a good?

I'd be interested to entertain your thoughts. Contact me here.

This column first ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on July 20, 2009.

ADDENDUM: Curiously, if not a little disappointingly, I had only one response when this article ran in the newspaper. Apparently New Bern's historians are not terribly interested in round-table discussions.

The one note I did get was a scolding one. The writer did point out the unpleasant possibility of what might have happened (or not happened) had the town not undergone major revitalization efforts a score of years back. However, she also dismissed my "what ifs" with something akin to disdain: "The 'what if' questions are more effective if they are in the future tense, not the past," she wrote. "'What if' can be the beginning of so many great things: What if... we had a public bus system, safe and well-planned bike routes, or a parking garage down town?" Her what ifs included small business encouragement, better schools, and so forth.

What if? Well, that bus thing sounds like it would nail an already-woeful-budget city with loads of new taxes; I don't know about others' thoughts on that parking garage, but I suppose it might make a handsome twin to the convention center which I fondly refer to as the airplane hangar (don't get me wrong--it serves a vital purpose--but couldn't they have at least designed it to fit in cosmetically to its surroundings...?).

I am a historian, not a civil engineer or industrial prognosticator. I deal in the past. That "past" can be ten minutes old, as far as I'm concerned, but it is past. These questions are all future-based with no present facts on which to build their possibilities. If history deals with the present (and it does), it is in how the past affects the present. The what-ifs of my Dear Reader deal with the future: what might be, potentially within our grasp. My what-ifs are beyond our grasp, for they deal with what could never be -- a "future-perfect" what might have been.

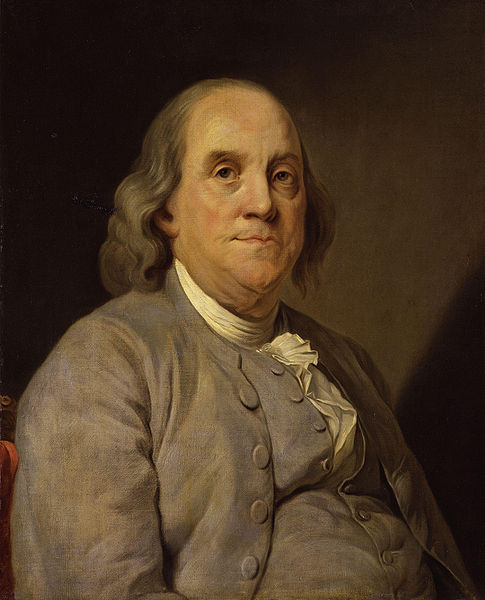

Benjamin Franklin and the Turkey

|

On this Monday before Thanksgiving let us examine the famous notion that Ben Franklin was pushing for Thanksgiving’s main course to be the national bird. Did Franklin actually think that big, bulbous, feathery and unintelligent mound we call a turkey should become the national symbol? The answer is an unqualified “yes and no.” The eagle was adopted as our national seal on June 20, 1782—along with that weird pyramid thing with the giant floating eyeball (look at it and wonder, what were our founding fathers smoking?). Franklin served on one of three committees that had originally been formed to draw up ideas for the seal. His own committee favored a picture of Moses closing the waters down on Pharoah (destruction of tyrants is obedience to God, the old deist proclaimed). No turkey was present, unless he was hiding under Moses’s robe. |

Seven years earlier he had written an article suggesting a rattlesnake as our national symbol—“her eye excelled in brightness, that of any other animal, and… she has no eye-lids. She may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance. She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage.”

It wasn’t until 1784, two years after the eagle’s adoption, that Franklin argued the case for Tom Turkey—and then only in a letter to his daughter. He mentioned a seal design in which he thought the eagle looked more like a turkey. This got him to thinking and comparing, so he penned his thoughts.

Franklin regretted the eagle’s choice because “he is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly… Besides, he is a rank Coward: the little King Bird… attacks him boldly and drives him out of the District.” Franklin was referring to the fact that small birds, trying to protect their young, will frequently chase eagles. They’re more maneuverable. What can the eagle do?

“For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America,” Franklin wrote. “Though a little vain & silly, [he is] a Bird of Courage and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.”

Take that as you will, but I suspect the old fellow was chuckling merrily as he wrote.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on November 23, 2009.