1752: Counterfeiters The crime could be lucrative but it laid waste the colonial economy—and those caught in the act wound up paying the ultimate price.

Take a tailor, a chemist, a blacksmith and a secret forge and what do you get? Funny money and a hemp rope collar. In colonial times North Carolina was in a desperate battle with counterfeiters. Governor William Tryon even took time out from addressing the Regulator crisis of December, 1770, to beg for action against the growing scourge, “an Evil absolutely destructive of Public Credit” that was “operating to the ruin of many honest homes and families.” Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette carried the story of some counterfeiters operating near New Bern in the late summer of 1752. Their names and professions were were Patrick Moore, tailor, Daniel Johnson, a “Chymist, or Doctor,” Bill Jillet, a blacksmith, and Peter Matthews, whose trade we do not learn. |  Above is pictured a Spanish Eight. All kinds of European currency were targeted for imitation by counterfeiters. |

Moore was a tailor at the house of one Richard Booker in Gloucester County, Virginia, who introduced him to the blacksmith and doctor and then recruited him to join their counterfeiting plan. Booker provided a boat and provisions to take the counterfeiting operation to North Carolina where they doubtless believed things could be better kept under wraps. The ultimate goal was probably to flood both colonies with multitudes of "funny money."

Booker stayed behind but Billet, Johnson and Moore (sounds like a law firm) sailed up the Neuse and tramped to the homestead of Peter Matthews, about thirty miles from New Bern. There, in a “great swamp,” they swatted mosquitoes and set up a forge. Doubtless Jillet, the blacksmith, oversaw the construction of molds that they made from doubloons, pistols, half pistereens and pieces of eight—all well-known European coins. They experimented with casting a few, but these were failures: though their shape was correct, their colors were off. It is probable that Dr. Johnson was here for this purpose: his knowledge of chemistry aided in finding the right metal mixture to make future batches a color-match.

But Craven County wasn’t made up of quite the mindless backwoodsmen they’d believed. The Gazette gives no name, but it does credit the Craven County sheriff with diligence in both capturing and keeping the scoundrels before they could perfect their product. Had they not been discovered when they were, the Gazette reported, they soon would have “plyed us plentifully" with counterfeit coins.

Counterfeiting was a crippling crime in a colony already in financial straights. Heavy taxes (someone had to pay for that “palace”!), cheating collectors, a lack of paper money and an economy strongly built around barter made life misery enough.

When Gabriel Johnston (governor from 1734-52) arrived here from England, one of his first acts was to put up a reward of £50 for the capture and prosecution of counterfeiters—and amnesty to any counterfeiters who would step forward and rat out their fellows.

It is perhaps a mlld irony that our own culprits—Moore, Johnson, Jillet and Matthews—were captured in the last month of Johnston’s life, August, 1752.

For some weeks they cooled their heels in the New Bern jail (spelled rather more colorfully as “gaol” in those days). The fact they stayed there was apparently a feat in itself, for the jail, in the words of the Virginia Gazette, “has hitherto been remarkable for letting Prisoners escape.”

We know nothing of their trial, but its result is known and expected.

Perhaps hoping for mercy, they confessed. Patrick Moore, the outsider in the whole affair, gave authorities the most background; his cohorts Jillet (the blacksmith) and Johnson (the chemist) placed the whole blame on him. Such is honor among thieves.

All were apparently remorseful, according to the newspaper report—remorseful all the way to the gallows, from which platform they met their Maker on October 16, a Monday (if you had to choose a day to die, wouldn’t you choose a Monday?).

Their escort to the gallows was the Rev. John Lapierre, who is of particular interest to us as he is buried in the little Bryan Fordham cemetery on Queen Street in New Bern. He was an early missionary sent by the Church of England’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to minister to French-speaking congregations around Charleston and Wilmington. He eventually moved himself northward until he settled in New Bern and married off his daughter to a merchant there.

The Gazette chose to make note of one Papist among the condemned: Dr. Johnson who “was very earnest and pathetic in his Prayers” for rebels who had been executed six years earlier in England for their parts in the rebellion of “The Pretender,” Bonnie Prince Charlie Stuart for the throne of England.

This article first appeared as two columns in the New Bern Sun-Journal on September 21 & 28, 2009.

1763: Founding Teacher

Thomas Tomlinson had his work cut out for him when he became the first headmaster of the New Bern Academy...

Thomas Tomlinson's grave is jut inside the entrance to the Cedar Grove Cemetery in New Bern, on the left. |

Education has a long and noble history in New Bern, the home of North Carolina’s first public school. January 1st 2009 will be the 244th anniversary of Thomas Tomlinson’s opening its doors to it in 1764. Poor Mr. Tomlinson was destined to have a rough time of it—life has never been easy for the edification-of-the-young crowd. He began his career as a teacher in Cumberland County, England in 1752. He must have impressed the parish, for the little St. James Church in Uldale carries a plaque in his honor to this day. In New Bern, the Rev. James Reed,

rector of Christ Parish, was seeking a good teacher. But North Carolina

being—shall we say?—a bit backwoodsy, had a |

serious dearth of educators. But Tomlinson’s brother (probably John Edge Tomlinson), a planter in Craven County, alerted the good rector to Thomas’s abilities. Reed pulled the necessary strings and it wasn’t long before Mr. Tomlinson was on his way across the sea.

He set food in the American

colonies in December, 1763 and began fishing about for students—male and

female. He “immediately got as many scholars as he could instruct,” Reed

proudly wrote his friend James Burton. In fact, he soon had so many he could not keep up

with them all. “He has therefore wrote to his

friends in England to send him an assistant,” Reed added (good minister were

far too busy to worry about grammatical tenses).

Reed

was proud of his new teacher—“During 11 years..I have not found any man so well

qualified,” he wrote the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Later,

Governor William Tryon would express equal pleasure.

Tomlinson’s

students seemed as fond of him as was the minister or the governor. He boarded at

the home of one student, who wrote, “Mr. Tomlinson keeps a good house

and is pleasant and kind. He has one other border who is also a student named

Baker from near Edenton. Mr. Tomlinson sees to it that we have our lessons done

each evening and that is the only problem of living with a schoolmaster. Other

wise it is alright.”

Early on, he was warned that the

parents in the colonies were overly indulgent of their youth: discipline could

be a challenge. Thomas tried to be patient, using “every little artifice to

avoid Severity” with his pupils, Rev. James Reed would report. However, one

student became so unruly that his teacher feared he was an endangerment to the

other students. He expelled the child and made “some little difficulties about

their Readmission.”

It was Tomlinson’s misfortune that

this was the child of one of the school’s most vindictive and powerful

trustees. It “was like the Sin against the Holy Ghost, never to be forgiven,”

Reed wrote. Bringing most of the trustees, whom Thomas later described as tame

and acquiescent, under his banner, the trustee began holding meetings without

notifying Tomlinson’s supporters. When a new school in Wilmington drained the

attendance at New Bern, Thomas asked the trustees to cover the cost of five

additional needy students to raise funds. The trustees refused, crying poor although the

treasurer had money enough to cover those students and more. As if to

add insult to injury, they revoked the tuition of the five needy students then

attending.

Though the parents loved Thomas, the

trustees finally found one, well in arrears on his tuition, who accused Thomas

of negligence. Not allowing him to

face his accuser, they offered his job to Mr. Parrot who refused and, being thus laid off, assisted Thomas as a volunteer.

Unable to fire him, the trustees

resorted to stopping his pay. Suddenly without income, Thomas was forced to

pressure his parents-in-arrears to pay up. Instead, making rears of themselves, they ridiculed him in front of

their children. Tomlinson resigned.

He set up a mercantile business in town married. He would be buried just

inside the gate of the Cedar Grove Cemetery, and would leave a large endowment to the

Uldale schools and the poor of Thursby parish in England. The endowment is still in use today.

This column first appeared as two columns in the New Bern Sun-Journal on December 29, 2008 and January 5, 2009.

1764: William Tryon's Atlantic Crossing

The man destined to be North Carolina's greatest colonial governor had some exciting times while crossing the sea.

A Governor Tryon story with which you may be unfamiliar: He arrived in Brunswick (a town the

British would later burn) on October 10, 1764. It had been an interesting

voyage. He’d been a passenger on Captain

Veriner’s snow (pronounced snoo) Friendship. With him was his beautiful and ambitious wife,

Margaret, their three-year-old daughter (also named Margaret) and the bachelor

John Hawks, who would later build Tryon Palace. A cry came from above: “Sails! A

sloop!” Sloops were small, one-masted

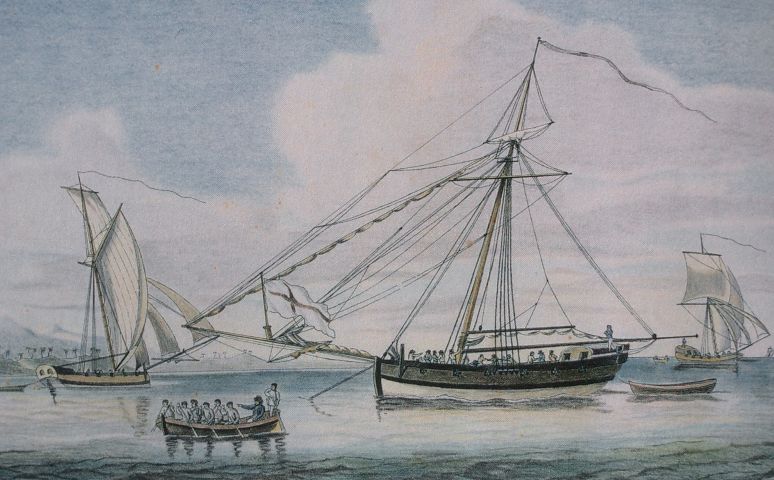

affairs. This one was lying dangerously low in the water. Her master John |  An 18th century sloop similar to the one whose crew and passengers William Tryon labored to save. |

Barns told Captain Veriner that she was floundering with five feet of seawater in her hold. For two days the crew had been desperately bailing and pumping, but the sea was gaining – the sloop was losing. The crew had already thrown more than half her cargo overboard in an attempt to lighten her and buy time. They begged Captain Veriner to take them all on board.

Veriner sent his carpenter across, but there was nothing he could do. Still, Veriner hesitated to bring them on board. The island of Madiera was nearby: could the sloop make it that far? Barnes was willing to try, but for safety’s sake one Mrs. Sealy and her son were sent to the Friendship, being ignominiously lowered into the longboat by being tied to a line.

One wonders what three-year-old Margaret’s thoughts might have been as she watched her father and others hauling a soaked, seven-year-old, wide-eyed boy over the gunwale. Did Mrs. Tryon hurry the mother and son below decks, shouting orders for blankets and hot tea while Miss Margaret clung anxiously to her skirts and stared in wonder?

On deck, Tryon and Hawks kept vigil with Captain Veriner and the crew. Madiera was hours away. Could the floundering Tyge last?

At midnight Barns fired his guns as a signal: the Tyge was going down – fast. Veriner hurriedly launched the longboat and, in four trips, ferried the men back to the Friendship. Tryon, New Bern’s Carolina Gazette later reported, “exerted himself greatly, and was very anxious the whole Time for their Safety.”

Quickly, now, with the high waves beating and washing her, the Tyge was pulled to her watery grave. Our greatest colonial governor watched, satisfied in the knowledge that he had helped to save lives.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on October 13, 2008.

1765: The Death of Arthur Dobbs, Colonial Governor

Maligned in his final years as a cranky old fool, Dobbs was in reality a fascinating man.

Arthur Dobbs, Esq. governed North Carolina from 1754-1765. |

|

He’d been led to believe that,

shortly after his arrival, the aged and ailing Dobbs would step down—but when Tryon was greeted by the man, he got a nasty surprise. “I waited on Governor Dobbs and

informed Him of the Honor His Majesty had conferred on me,” Tryon wrote in a

hot letter to Earl of Halifax…

|

Dobbs was unruffled by his young protégé’s anger: he was used to having his own way. Over the next few months Tryon was introduced to the legislature and then, “wanting Employ,” he and his wife toured their new colony over the winter months. We might think winter to be a strange time to do your traveling, but in Tryon’s eye, the summer was just too far away—and a deadly season for traveling, with yellow fever around.

His travels must have done him good, giving him important contacts and facts that would stand him in good stead over his coming six years’ rule.

Finally, Dobbs set a date for his departure – April of 1765, though he described it to Tryon as a “leave” rather than a resignation. Having the typical old-man’s disease of “I can do it myself,” he insisted on doing much of his own packing. The doctors were not happy and tried to slow him down; the old Irishman ignored them. “His physician had no other means to prevent his fatiguing himself,” Tryon wrote the Earl of Halifax, “then by telling him he had better prepare himself for a much longer Voyage.”

On March 25, while packing books, he was struck by a seizure. Two days later, in his young bride’s arms, he died. Justina wrote a letter to inform Dobbs’ sons in Ireland: “I have lost one of the best and tenderest of husbands and you a kind and most affectionate father.”

He was buried in the church grounds in Brunswick, where he had lived (he had earlier removed the government from New Bern’s shoulders because he didn’t like the climate there). No clergyman could be found to conduct his funeral and, today, no one knows the location of his grave.

Though he did not leave the impression on Colonial history and politics that Tryon would, Dobbs was still a capable and fascinating leader, a warring adventurer who left his imprint in the science of botany. We shall return to him again.

This column first ran March 24, 2008.

1767: The Great Wolf

On May 19, 1767, Governor William Tryon arrived in the North Carolina hamlet of Salisbury where he staked his colony’s peace on a border treaty with the Cherokee Indians. Salisbury? Staked? Oh, never mind. It was an attempt at peace seventy-one years before

President Andrew Jackson would immortalize his administration with the horrific

Trail of Tears. In these days, the British saw the

Appalachians as a kind of permanent barrier to mass settlement by their white

subjects; it made a convenient line of demarcation between Europeans and native

Americans. Of course, the colonists who were ever land-hungry resented these boundary settlements—perhaps that’s one reason the Indians tended to

side with the British during the Revolutionary War. | .jpg) For his work in settling a boundary to protect them from European incursions, the Cherokee gave William Tryon the name "Great Wolf." Photograph courtesy of the First People website. |

For some years whites had been passing into the Cherokee’s territory, building homesteads in their ancestral hunting grounds. The Indians were getting rather miffed.

John Stuart, the king’s agent for Indian affairs in the

Carolinas, had pressed South Carolina to set an official border over which

whites could not encroach; Tryon thought this a fine idea. Indian trade was

advantageous for both sides; Indian wars were not.

Tryon convinced the assembly that a

border was a wise thing so they advanced him £100 toward his expenses. He

loaded up a train with gifts and supplies then, with his good friend Edmund

Fanning, his most trusted officer Hugh Waddell (a Wilmington man) and

two regiments of militia from Rowen and Mecklenburg Counties, he began his

westward trek. He would not see home again until June 13.

He later described the costumes his

militiamen wore: “Each Man had his Rifle Gun, and their general Uniform and

appointments were a Carters Frock, Indian Match Clouts (in lieu of Breeches)

Moccasons (for shoes) and Woollen or Leather Leggins; the latter were necessary

to prevent the bite of the Snakes of which We saw a great Plenty.”

On that last sentence it is

interesting to note where Tryon set his emphasis via capital letters!

His party traveled over the border

into northern South Carolina where, at the Reedy River, he met with the

Cherokee chief Ustenuah Ottassatic (thankfully for our tongues he was also

known as Juds Friend). Feasting, gifts and negotiations began on June 1. Tryon

gave a speech to his Indian guests, concluding that he would “most faithfully

adhere to [the boundary] and… pursue every measure that may strengthen and

brighten the Chain which holds fast that Peace and Harmony which at present

happily subsists between us.”

“We have met here and smoked

together as brothers,” Juds Friend stated the next day. “the white People and

ourselves should be all one,” he added, but he included a show of his grasp on the trustworthiness of white men’s treaties: “I hope our Talks will be

straight and Right.”

Surveying work began on June 4 and

the governor hung around two days to watch it unfold. Then he headed for home on

the sixth.

On June 13 an agreement was signed:

the border would run northeast from the northwestern corner of South Carolina,

passing over the top of Tryon Mountain (roughly the Asheville area), to Col.

Chiswell’s lead mines in Virginia.

The Indians honored Tryon with a

new name, Great Wolf. He arrived home, weary after a 843 mile trip and minus

his horse, which had been stolen somewhere along the line.

Tryon’s trip was not very popular

with the colonials who complained of its cost; some settlers were removed from

the Cherokee side of the new boundary and of course that didn’t set well

either. It is unlikely that a boundary aimed at aiding the Native Americans was popular with most people, even on

the coast: the Tuscarora War may seem a distant event to us, but it had ended

only 52 years before Tryon’s trip… there probably survivors of the

September, 1711, massacres who were still alive.

Tryon was under direct orders

from England to honor the treaty. “I must particularly recommend to you, that

this necessary Work may be executed with Candor and the Stipulations observed

with good Faith,” the Earl of Shelburne wrote him from Whitehall in England.

“For nothing can more effectually conciliate the minds and Affections of the

Indians, than a Measure which must convince them that we mean to protect them

in the peaceable Possession of those Lands which are necessary for their actual

Subsistance.”

It was a border that would be

honored, for the most part, until Andrew Jackson arrived in the White House in

1829.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on May 19, 2008.

1770: Colonial Medicine

Medicine in our founding days was not a pretty picture.

The fellow shown above is enjoying having his leg amputated on a pleasant 18th century afternoon. | Sometimes I look upon the simplicity and values of our colonial days with envy—at times when my romantic side is standing in the forefront and my realist side is back in the closet, bound with padlocks and chains. My Caucasian skin helps blind me in these moments (no African American in his right mind would wish to live in those days); I also forget that I am a commoner. In 1770 I would probably have been illiterate. I would have smelled bad, too, though I doubt I would have had the sense (olfactory or otherwise) to realize it. My romantic side also conveniently forgets about the state of medicine. Given the state of cleanliness (a layer of dirt was considered healthy) and anesthesia (ana-what?), a bout with surgery was comparable to the Inquisition. |

New Bern had no shortage of doctors. Among them was Alexander Gaston, a former British naval surgeon who had settled here for his health. Many a patriot was glad of his bandages, though not of his probes. Doctors and surgeons who’d honed their skills on the bones of sailors and soldiers were among the most skilled. New Bern was lucky to land this guy.

Doctors in America rarely had

formal education in medicine—all the medical schools were in Europe. The town

doctor probably learned his trade from another doctor. Possibly he learned it

from books. Many doctors of the day (Voltaire estimated 98 out of a hundred)

could have been described by any self-respecting and vocal mallard: quack,

quack, quack.

When you got sick, mom tended you

with herbs and medicines grown in the garden, and sometimes with hocus-pocus

learned from the past. When her efforts failed a doctor was called in.

Depending on what you had and the dim light of knowledge he carried, he

proceeded to either cure you or kill you. If he decided surgery was needed, he

pretty much turned up his nose and called in the guy who cut your hair and

curled your wigs. That’s right: the barber. He shaved you, pulled your teeth, sawed off your festering arm and (as evidence in the Jamestown Colony shows)

occasionally even handled a bout of brain surgery. For amputation a kind of

hacksaw was used and, as likely as not, a red-hot iron to cauterize the flesh.

To prep you for surgery, you were

pretty much tied down. If you've seen the fifth episode of the John Adams series, you've seen a good example in Adams's daughter who underwent a mastectomy in her bedroom. A good dose of whiskey hopefully numbed the pain, for

anesthesia would not be around until after 1839. The operation was agony, but

at least it was quick—too slow an amputation resulted in shock and death. For

other surgeries requiring more delicate care—say the cutting out of foreign

objects, you just had to whistle (or scream) as they worked.

Once it was over there were only

herbal medicines to ease the pain; there was practically nothing to stop the raging

infection brought about by dirty instruments and hands. With a plethora of

possible complications, a man who lost his leg also had a 75 percent chance of

a one-way ticket to the Promised Land.

The prominent theory of the day was

that “bad blood” caused numerous health conditions, from minor, chronic

headaches to life-threatening ills. And so surgeons loved to cut and bleed

their patients—with the bad blood gone, “good” blood would be produced. With

this belief wedged in their heads, surgeons spilled their patients’ life and

slew them by the thousands. George

Washington was just the most famous of their ignorance.

Medicine in the eighteenth century was not quite the vast field of darkness that we sometimes imagine. Huge strides were being made in Europe—forceps came into use in childbirth (1752), successful cataract surgery saw light (1752), orthopedics was born (1780), and even in Governor Tryon’s day inoculations for smallpox were starting to spread, saving lives and lifelong scars.

By English law, barbers

and surgeons were separated in 1745; in London a surgeon could not work until

he’d been passed by a committee of master surgeons at the Royal College. But

New Bern was no London. The best of the doctors and surgeons were trained medical men—we were lucky to have a couple of those.

This column first ran April 7, 2008.

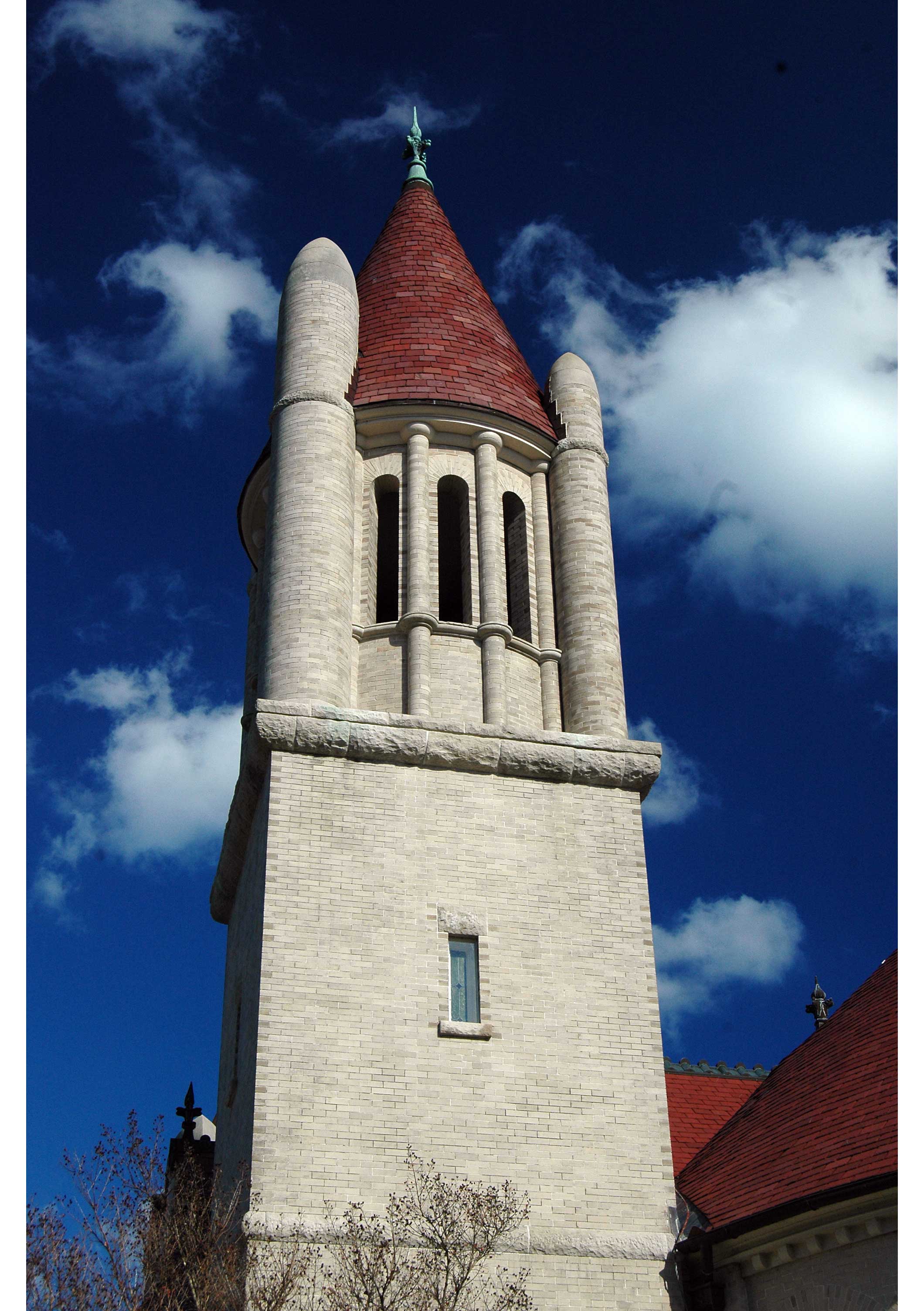

Centenary United Methodist Church as it stands today. Ah, Christmas! On this day, the children you couldn’t drag out of bed on a weekend will be dragging you out before seven. Eggnog, a meditation at the crèche, and the family will gather around the Christmas tree, beautifully lit and decorated until you reach its chaotic bottom fourth —for, if you have an ambitious 20-pound cat like we do, he will have undecorated everything he could reach. |  |

What are you getting for Christmas?

In 1772, New Bern got a church.

Until that year the “Shouting

Methodists” had no meeting place in which to display

their enthusiastic faith. That “shouting,” by the way, was a term invented to

insult them, but the Methodists embraced it—the story as the Brits mocking us with

“Yankee Doodle.” We rather enjoyed the slight and piped it so much in battle

that they had the tune haunting them in the same way that “Gilligan’s Island”

gets stuck in your head.

John Wesley, reluctant founder of

the Methodist church, believed that “true Chrsitianity fulfilled all of a

person’s deepest, tuest desires, making the Christian a happier, more

productive person,” according to a December 8, 2007 issue of Christianity Today. To many, it was a bright alternative to the more

somber Presbyterian, or the officious Anglican, ways.

Wesley never came to New Bern, but

an associate of his, Rev. Joseph Pilmore, did, wandering into town from his

usual Philadelphia and New York City haunts to spread the good news and – well

– to do some shouting and stir up a little spiritual falling down. He spoke to the citizens on

Christmas day, and from this event Centenary United Methodist sets its birth.

His Good News wasn’t good news to all. One of the city’s most prominent men, Anglican missionary James Reed, looked upon these fellows and their “enthusiastic ranting” (Reed’s words) with deep suspicion. Still, Rev. Pilmore was well-received, and his visits were followed by other circuit rider—preachers on horseback with missions in their hearts and Bibles in their saddlebags. Eventually, Francis Asbury, head of the American branch of Methodism, would preach in town 14 times.

Centenary is one of the oldest

Methodist congregations in the south. It built its first church (the city’s

second) on Hancock Street in 1802 and its current building, on New Street in

1904. This gorgeous building will merit a column of its own.

Merry Christmas to you all, and

remember to honor the Christ Child in service tonight. And special good wishes

to you who will be doing candlelight to the Christmas Child in New Bern’s own

Christmas church.

First run December 24, 2007

Contact me at: newbernhistory@yahoo.com.

1780: Mr. Williams’s Ball

When the river froze over and shut down his ferry business, Mr. Williams decided to celebrate.

Today if we want to cross the Neuse we’ve got that big, fancy bridge (above and below); but in the 18th century the only way across was a ferry like the one Mr. Williams ran--unless the whole river froze over. (Pictures by the author)  | As a child in Pennsylvania I honestly believed that if you stepped over the Mason-Dixon line the temperature would leap to 80 degrees and that you’d find yourself in the midst of palm trees—even in the middle of January. Ignorance was my strong suit. I will confess that heat is my friend: when folks ask

why I moved to New Bern back in 1995, “January” is my stock answer. That isn't to say I completely escaped frigid air. We do have our cold days. The record low temperature for January 30 in New Bern, by the way, is a frigid 14 degrees Farenheit (1986). It’s enough to put a Carolina squirrel into false hibernation. We have a history of significant cold snaps. On this day in 1780 the river froze so solid that people could walk across it. You would think the ferrymen would have been depressed--frozen rivers equal frozen business. |

But ferryman Benjamin Williams, who

kept a ferry house on the north side of the Neuse, was not that way. When he saw his ice-bound ferry barge and gazed out across that icy vista he did not wail. Perhaps he tossed the cat out to see if he went through the ice. Next, he maybe hurled out the dog and,

after laughing at the spectacle of the poor creature trying to gain its footing for a while, he possibly took a few tentative

steps of his own. Jumped up and down. Danced.

This was history: he couldn’t remember the river freezing like this before. New Bern ice is usually that thin stuff that forms out from the bank—crystal-clear and brittle, with an outer rim of frost. Bubbles pass beneath; it makes an art form of itself. But you wouldn't want to walk on it. Not even a rat would risk his weight.

But Mr. Williams was looking at heavy-duty H-2-0.

Mr. Williams, or so historian John

Whitford tells the tale, declared a celebration. Being one of the “gayest of

the gay,” Whitford thought (it simply meant “happy” then), he sent word out

that he would host a feast and ball. In those days, ferries were not only a means of transportation, they were also a center of entertainment. Woe to the ferryman who got his people across without offering a place to stay the night: a room, a meal, perhaps some entertainment. So we can be sure that Mr. Williams had ample room.

The ladies of the town gathered at

Clark’s Ferry House (where that was I do not know) and marched by torchlight procession to the ballroom at the Williams’s home. They arrived, “their faces…

dotted with soot, and also the white dresses… thus giving additional charms to

beauty, in the opinions of those present, and it must have been so, as after

that it became the custom, which was continued for a while, to make servants

shake lightwood torches round ladies preparing for balls.”

Along with setting a trendy new fashion (that doubtless made the washerwomen's vocabularies enlarge in a not-nice way), the ball was a success "the notoriety of which has reached through more than a century for its success and elegance," Mr. Whitford wrote. Two centuries now. And a quarter.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on January 28, 2008.

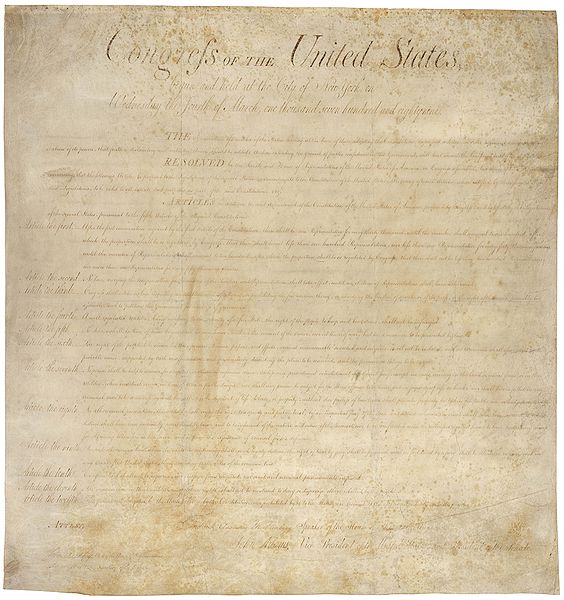

1789: North Carolina Signs the Bill of Rights

We've always taken the slow and steady course in making major decisions.

As we approach Christmas, we think of the beautiful gifts we have received. Of course the first one that comes to mind is America’s Bill of Rights. Okay, maybe not. When I was nine my

Christmas thoughts involved a GI Joe Scuba Adventure set. It included this really cool scuba-diving sled that actually worked. For the next several days GI Joe fought the forces of freedom in our bathtub while the water bill skyrocketed. Nowadays my nativity thoughts are of the

Christ Child. Still, Jesus was not born in New Bern and in my childhood days I was only vaguely aware of North Carolina, much less New Bern—and besides, I need a tie-in. So lets run with the Bill of Rights. North Carolina was the next-to-last

original colony to join the union; she was also the last to leave it in 1861 (North Carolina: The We Get Around To It Eventually State). But she was the third to adopt the Bill of Rights. Here’s the nutshell: In 1787 our leaders gathered in Philadelphia to draw up our nation’s constitution. New Bern’s Richard Dobbs Spaight, still thirteen years from his destiny with a duel and John Stanly’s bullet, was one of the signers. |  That famous piece of paper (now housed in the National Archives if you're interested) was written in part due to a request of the North Carolina assembly. PD-USGov-NARA; NARA [http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/charters_downloads.html |

A year later our state assembly received the Constitution in hopes of approval (its acceptance resulted in statehood). Being politicians they debated for eleven days and finally shipped the whole thing back: it was nice, they said, but the anti-Federalist party was concerned about the rights of men. Could someone possibly add a Bill of Rights to the whole thing? By November 21 of ’89 this was not a done deal, but at least it was taking place (a doing deal?), so the Constitution was passed and North Carolina became State Number Twelve. Rhode Island, which had probably been misplaced by some thoughtless Congressman, didn’t become State Number Thirteen for another six months.

The Bill of Rights, finally presented to Carolinians, was approved on December 22, 1789, just in time for Christmas.

North Carolina was strong on rights: only Maryland had been more open to religious freedom in her founding days; and our state assembly had adopted a Declaration of Rights for personal freedoms back in 1776. Among other things this granted the right to be confronted with one’s accusers in cases of prosecution; it denied a state’s right to force you to house soldiers and required judges to impose a reasonable bail; it included the right to bear arms, freedom of the press, and of course the right to vote. So long as you were over 21. And male. And free. And an owner of significant property. Okay, so suffrage thing needed a little work…

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal December 22, 2008.

1790: A Day at the Races

Colonel John Whitford, that curmudgeonly soul of 19th century New Bern, once told a charming tale about an old Baptist preacher: His son had snuck off to enter the family mare in the races—on a Sunday, at that. The preacher dealt brimstone on the boy for his disobedience but finally hesitated to ask who’d won. “Oh, I did,” the son said. “That’s right, if you will race beat them if you can,” the preacher softly replied. He told the story while relating the “deserved flogging” his grandfather, Elijah Clark, used to receive for riding in the races on Sundays. “Perhaps,” Whitford wryly noted, “the horse he mounted was not successful.” We had a horse race track, way back in the 1700s: it is noted on the map drawn up by Claude Joseph Sauthier in 1763. Finding it today would be a grave task. I mean that literally, because, according to Whitford, it was pretty much where Cedar Grove Cemetery stands today. William Attmore, a journal writer from Philadelphia, made several comments about our racetrack when he visited the town in 1787. Four or five horses ran each race, jockeyed by “young Negroes 13 or 14 years old,” riding bareback. He was not impressed. "Large numbers of people are drawn from their business, occupations and labour, which is a real loss to their families and the State," he growled, noting as well "wagering and betting; much quarreling and wrangling, Anger, Swearing & drinking... I saw white Boys, and Negroes eagerly betting 1/2 a quart of Rum... as well as Gentlemen betting high." |  You will still find horses in New Bern today, but their lives are much more mundane. Photo by Bill Hand |

One of those high betters was Dr. Edward Pasteur, and his “celebrated horse Snap-Dragon” (the quote is from Whitford). The horse was a descendant of Collector, a sire Pasteur had purchased from John Hawks, builder of Tryon Palace. Pasteur would finance a privateering boat during the War of 1812. That boat, which would bring him a fortune under its captain Otway Burns, was named Snapdragon, very likely in honor of this horse.

Horse races tended not only to result in wagers and vast spillage of rum; but in broken bones and contusions as well. Attmore wrote how “One of the horses at starting, [ran] violently amongst the people that sat in a place of apparent security, it was precisely the spot where I thought there was the greatest safety, for foot people.”

He reported a more curious incident from the previous day: “One of the riders a Negroe [sic] boy, was, while at full speed thrown from his Horse, by a Cow being in the Road and the Horse driving against her in the hurry of the Race—The poor Lad was badly hurt in the Head and bled very much.”

Such are the wages of sin, as the old Baptist preacher might say. Especially if you don’t win the purse.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on January 21, 2008.

Margaret's room as imagined at Tryon Palace HIstoric Sites and Gardens. | Valentine's is the

perfect week to look at the tragedy of poor little Margaret Tryon. She was born on June 28,

1761, in London and was a toddling three-and-a-half when her daddy, William

Tryon, crossed the Atlantic in 1765. He had just been assigned lieutenant governor of North Carolina and would take over as governor in 1765. We have a couple of

his letters that suggest a fatherly affection. “There is a Piaza Runs Round the

House both Stories of ten feet Wide,” he wrote a friend of his first American

home in Brunswick, near Wilmington, “with a Ballustrade of four feet high,

which is a great Security for my little girl.” He would also brag of his

daughter’s strong constitution when he, himself, was sick as the proverbial

dog. Apparently her parents could sometimes be controlling. Lady Anne Blair gave this anecdote of an eight-year-old Margaret visiting Williamsburg: "[The Tryons] have a little Girl with them that is equally to be pitied, the poor thing is stuck up in a chair all day long with a |

What is it with those colonials and their obsession with capitalizing common nouns?

Big events would take place—a move to New York in 1771, a fire in which she nearly died, and the beginning of the American Revolution. Eventually, the Tryons resettled in England where William died at the relatively young age of 58. Margaret herself would become a maid of honor to Queen Charlotte. The famed journal writer Fanny Burney described Margaret as one who “chatted incessantly”; William Smith, a friend of the Tryons who’d fled New York and kept up with the family in London, alluded to Margaret’s friendship with actresses who thrived on the boards at Drury Lane.

Eventually she fell in

love with an officer in the Life Guards. Apparently her mother did not approve

and refused to let a marriage take place.

Like a heroine in a Moliere play, Margaret was determined to have her

way: in the summer of 1791 she and her soldier decided to elope.

It says something about

her mother’s control that Margaret, who was now thirty, felt she had to take

such drastic steps. And a drastic step it was: From her window, she lowered a

rope ladder to her lover below. Climbing down she lost her footing and

fell—impaling herself on the iron palisades of a fence as her horrified soldier

watched. Their Moliere comedy had turned into a drama smacking of Racine.

All in all, hers was a

most romantic life—her family was influential and as a child she witnessed a nation’s troubled birth. Her talent and position led her to life

in the court of the king and the heady airs of Drury Lane. It is a shame we

have so little information about her mysterious soldier, or their whispered promises

and stolen kisses before the boney hand of death stole her away.

This column first ran February 11, 2008.

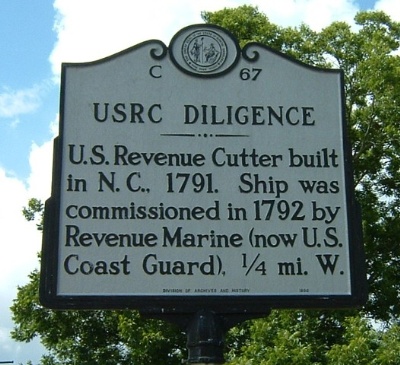

1792: The USRC Diligence comes to town.

| At the corner of East and South Front Streets you will come upon one of New Bern’s ubiquitous historic markers, this one regarding the USRC Diligence. USRC—that means United States

Revenue Cutter, boats under the same named service that was started on August

4, 1790, by Alexander Hamilton. In those halcyon days after the American Revolution, our founding fathers came upon the strange conclusion that a navy was something the nation could do without, so they disbanded it after the war. By 1790 Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the treasury, had woven a number of impressive impressive tariffs and other shipping-related revenues. But Mr. |

Hamilton was finding it difficult to convince ships to pay up without a navy. But there was no budget to build a navy up. He did the next best thing, establishing on August 4, 1790, the cutter service and authorizing the construction of ten cutters whose job it would be to police the waters, protect sailors, and collect dues. This was the precursor of the Coast Guard.

These were small craft sailed by

small crews with particularly light arms—but they were surprisingly effective.

The first cutter was probably the Vigilant, launched in 1791 in New York. Our own cutter, the Diligence, was built in Little Washington in 1791 and found

her first service in New Bern sometime in 1792. Her first master (through 1796

when he strangely disappeared) was William Cooke.

She was a schooner of 40 tons,

apparently manned by a small crew of four officers, four enlisted men and two

boys. Her armament consisted of muskets, pistols and a broad axe or two. Like

other revenue cutters, the Diligence was

directly answerable to the Customs House in town, though Master Cooke had a lot

of maneuvering room when it came to deciding what he actually wanted to do. For

a year he patrolled local waters, collecting customs fees and keeping an eye

out for illegal activities and piracy.

In 1793 the ship changed home

ports, moving south to Wilmington, and her very short career with New Bern

history was ended.

We don’t know much about the Diligence’s service, beyond her being involved with the

recapture of the San Jose, a

Spanish vessel that had been taken by the French privateer Amiable

Margaretta in 1793.

The Diligence was sold out of service in 1798 for $310.

This article first appeared in the New Bern Sun Journal on May 18, 2009.