1861, April: Fort Sumter's Fall is heard in New Bern.

I had always heard and accepted the idea that New Bern was strongly pro-Union before the Civil War. But I’ve been rooting through the Newbern Daily Progress of 1861, and I’m darned if I can find much evidence of Union sentiment there One must read papers with a grain

of salt—especially in a day when much of the news reported was learned from

travelers on trains, and when (just like today) the convenient “facts” were

often colored by the intentional omission of inconvenient ones. North Carolina was the last state to actually secede—and it took two

attempts to do that. An initial |  |

election was held on February 28, 1861, to determine whether the citizens wanted to hold a secession convention at all. State-wide, it was opposed—but New Bernians favored it by a margin of almost two-to-one. The state actually seceded on May 20, by the way, and a New Bern representative, John D. Whitford, headed the committee that designed the new confederate state’s flag.

Strong evidence of New Bern’s sentiments came

upon news of the fall of Fort Sumter. The Progress reported:

Great excitement

prevailed.

The extra train got in

between 9 and 10 o’clock Sunday night and was met by a hundred or two men who

received the news with shouts of applause!

At 10 o’clock, seven guns

were fired in honor of the seven Confederate States and bonfires sent up a

brilliant volume of smoke and flame.—Soon thereafter, “The Father of the

Faithful” [Lincoln] was hung in effigy on top of the ruins of the old court

house.

We passed yesterday

morning about 10 o’clock and he was still dangling in the air with a pasteboard

upon his brow, in large letters, was the following inscription, “May all

Abolitionists meet the same fate.” About a dozen little boys were busy pelting

him with stones…

The Elm City Rifles—a local militia, which

would fight nobly through the war as part of the Second North Carolina

Regiment, held an impromptu parade with New Bern belles smiling and waving

handkerchiefs from their doors and windows.

President Lincoln’s demand, a day or two after,

that North Carolina send 2,000 men to fight for the Union finalized North

Carolina’s mind, but it was the excitement of the fall of Sumter that cemented

North Carolina’s exodus from union.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on April 13 2009.

1861, April: Lincoln calls for troops and North Carolina reacts

One could argue that North Carolina entered the Civil War on April 17, 1861, for on that day Governor Ellis made an official call for troops. Event birthdays are always hard to pin down in North Carolina, because the state just can’t make up its mind about anything in one day. Voters had vetoed a bill to consider secession on February 28, as we have seen, for the men of the state weren’t overly anxious to undo all the sacrifices their fathers had made for a union just because South Carolina was overrun with fire-eaters. They were nervous about the slave issue and Black Republicans, but not so nervous as to join the Confederate cause. But the union’s attempt to supply Fort Sumter, and Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion made Tarheels do an abrupt about-face. They would not actually vote to secede until May 20—but dissolution was, for all practical purposes, a done deal before April was half-way gone. We were the last to secede, perhaps, but not the last to adopt a diet of fire. New Bern sent numerous men to the war—a stroll through Cedar Grove Cemetery will bring up a number of veterans’ gravesites. A number of New Bern companies such as the Elm City Rifles and the Beauregard Rifles helped fill the ranks of several regiments. |  Lincoln: He wanted North Carolina to hand over troops for war--and he got them. But as enemies rather than friends. Picture in the Public Domain. |

North Carolina was the Confederacy’s breadbasket—and her main supply depot, source of clothing, and provider of men and blood. With a white population of 631,000, North Carolina mustered some 125,000 soldiers for the war—significantly more than any other state. Her casualties were also far greater: 20,602—more than any other Southern state.

The first official southern casualty of the war was North Carolinian Henry Wyatt at the Battle of Bethel, June 10, 1861. The highest casualty rate of any regiment was the 26th North Carolina: 714 of its 800 at Gettysburg. On roll-call the second day of the battle, Company G only had one man to answer, and the sergeant gave roll-call from a stretcher.

Ours were the first regiments in battle (Bethel), penetrated most deeply into enemy lines at Gettysburg and Chicamauga, fired the last salvo before Lee's surrender at Appamattox--and were the last to disband after Lee's surrender.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on April 20, 2010.

1861: Confederate Yankee in Christ Church's Court

Rev. Alfred Watson was rector of Christ's Church in New Bern in 1861. The church's steeple is shown in silhouette above. | Reverend Watson hid the communion set below, given to Christ's Church by King George II, in a Fayetteville closet during the war to keep it safely out of marauding Yankee hands.  Some ministers proved to be a great disappointment in the Civil War (see the story of Rev. James Sinclair below). But there were honorable men of the cloth as well, among them the Rev. Dr. Alfred Augustin Watson, who couldn't help but become a strong and virtuous man dragging around a name like that. A Brooklyn native, he had taken his first orders with a Plymouth, North Carolina church in 1844. Twice he was asked to take the reigns at Christ Church and twice he refused before finally accepting in 1858. Local historian Gertrude Carraway declares he rapidly became “One of the most beloved of all local and East Carolina |

churchmen.” Over the years he would show such value and discernment that, in 1884 he would become the first bishop of the Eastern North Carolina Diocese of the Episcopal Church.

When war broke out, New Bern's men turned

out to form a number of companies of soldiers to fill the regimental ranks. Three local militias helped form the Second North

Carolina and Rev. Watson signed on as regimental chaplain. The

vestry asked him to keep his rectorate and so he remained on the vestry's books until the town’s fall. Rev. William Wetmore (sounds like the name you'd give a sitcom sidekick) was hired

in September of ’61 to assist while Rev. Watson was off at war.

Watson did more than watch the

soldiers’ spiritual needs: he watched the enemy's movements as well. “His information of the topography of

the country was of great value to our commanding officer,” Captain Matthew

Manly of Company D remembered of his chaplain's scouting work. “He had the profound respect of every man.”

Watson could not return to New Bern

after her fall, though Wetmore hung in for another year. Union chaplains were

placed in charge of Christ’s Church. Midway through the war Watson would become rector of St. Paul's in Wilmington, where he remained for some years.

Christ’s Church maintains a

valuable communion service donated by King George in 1752. A popular story

tells how Rev. Watson spirited it out of town, carrying it to Wilmington for

safekeeping. Later, the Rev. Hoke

watched over it in Fayetteville, hiding it amidst old rubbish in a closet.

Yankees entered the town, searching for loot, and dug through the closet. Seeing all the rubbish they looked nor further and missed a most valuable prize.

While Carraway does not mention this event in her fine church history, a 1922

booklet on the church does. It certainly seems within his character.

True or not, the legend seems to reflect the real character and style of this

interesting man.

This column first ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on January 19, 2009.

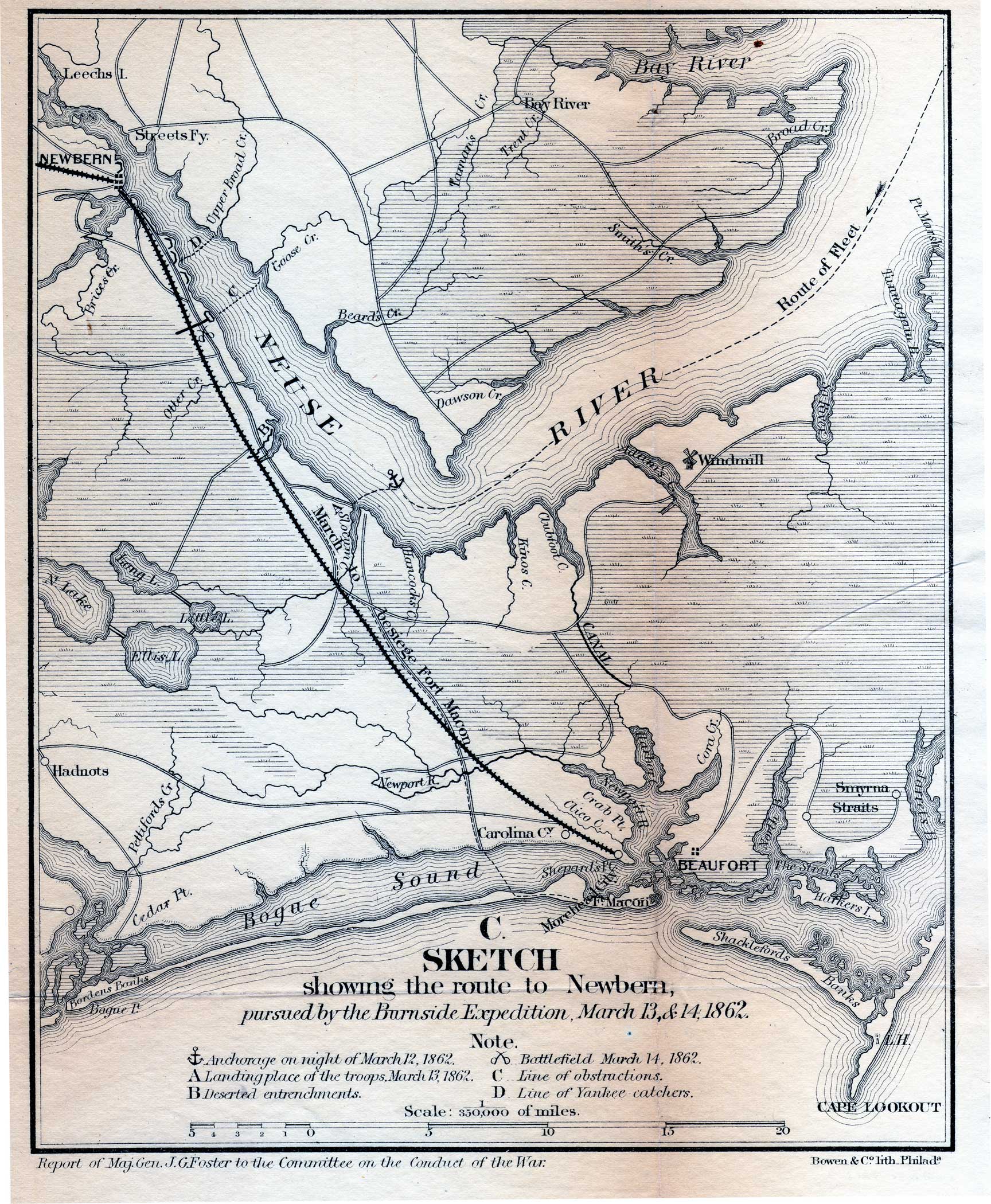

This map shows the route General Ambrose Burnside took on his way to the capture of New Bern on March 14, 1862. | Among the many things that went wrong in the Battle of New Bern for Confederate forces was the error-based expectations and the performance of this Union-leaning minister-turned-Confederate-soldier. New Bern fell to Union forces during the Civil War on March 14, 1862. I could pour lots of numbers and factoids about the fight on you, but I'm far more interested in the people involved. Statistics can be dull, you see, but people rarely are. Take Colonel—Reverend Colonel—James Sinclair. A Presbyterian minister in civilian

life, he was a bit of an anomaly in New Bern at that time: a |

Confederate who had actually experienced a battle.

Originally a chaplain with the Fifth North Carolina, he’d seen action at First

Bull Run (Manassas) the previous July. This “fighting chaplain,” the story

went, had led the men of the Fifth in several advances on that bloody field; that General James Longstreet was so impressed after the fight that he offered him a

position in his command.

When he signed on to the Thirty-fifth North Carolina, this story circulated and his fellow officers voted him colonel in command... it was an obvious choice.

New Bern was a definite underdog in the coming battle: outnumbered three to one, with a unit of

barely-trained local militia manning a key point of the defense, disaster

seemed pre-ordained. Also, the commanding general—Lawrence O’B. Branch—was a

politician with absolutely no military training. He had good, trained men under

him, such as future heroes Henry Burgwyn and Robert F. Hoke, for advice. But

even those men had never “seen the elephant”—that is, they’d never actually

fought.

A few miles below the line of the current New Bern Battlefield was a powerful line of works called the Croatan Breastworks. Branch believed he could hold that line against all comers with just two thousand men and a couple of cannon. But behind the line was six miles of riverfront property that could not be defended. Yankees could land anywhere along here and take the Croatan line from behind.

To compensate, Branch dug rifle pits on either side of the line. Rising over the ridge 25 feet above the waterline, he felt he could make any attempted landing very costly. He ordered Sinclair and his men here, assuming such a brave and experienced colonel would hold the line. Reinforcements would soon be sent.

General Branch must have pinned a lot of hopes on his fighting reverend: he was to open fire on any attempted landing by Yankees, and to protect the flanks of two well-drilled but inexperienced regiments (the 7th and 26th) that were manning vital Croatan breastworks near the expected landing site. Eventually he would probably have to pull back--the enemy was bound to land upstream and attempt to flank him, but still the three regiments could buy time at a dear price to the enemy. Trains were waiting to hurry them back to the Thompson line.

General Branch and Sinclair’s men felt secure in their leader’s experience and bravery. But there was a fatal flaw in the making: Sinclair’s story was only partially true, and his loyalty to the Confederate cause highly negligible if not border-line treasonous. The battle’s failure—rather than its hopes—would lie to some extent with him.

Sinclair listened to the voices of his enemy on their boats that night and it must have spooked him. When some Union gunboats started firing on the pits, instead of ordering his men to "hunker down" he told them to retreat. No men were lost in the shelling, though one was killed and two wounded as they fled the line. The reinforcements arrived about this time and, finding the rifle pits abandoned knew it impossible to hold the Croatan line. Thus—much to the later astonishment of the Yankees—the strongest fortifications were never manned.

Sinclair’s men were now with the

main force holding the Fort Thompson line (now the west side of the Fair Grounds and by the Taberna development), where the Battle of New Bern took

place on March 14, 1862. They were placed near the inexperienced militia—a

small army of citizens recruited from town just two weeks earlier and

manning—bizarrely enough—the weakest point of the Confederate line.

Early in the fight, Sinclair’s men

saw a wondrous sight: the Union General Reno suddenly appeared, standing within

easy shot, talking with his officers. The men wanted to pick him off but

Sinclair would not allow it, declaring such an act ungentlemanly. A couple of

hours into the fight the Union forces routed the militia. Rather than taking up

the slack some of the men of the Thirty-fifth joined them in their flight.

Sinclair briefly attempted to keep the rest at the line, then gave it up

and sent up his second order of retreat. Once again their flight left the

rest of Branch’s army exposed from the flank, and the battle was

essentially lost.

Let’s conclude with “the rest of

the story.”

General Branch must have been greatly disappointed in a man who’d come so

recommended. We know that Sinclair’s men were upset: they blamed their flight

on him and voted him out of his colonelcy within days. Perhaps their blame was

well-placed: the regiment would fight bravely in the future.

He had gained his position in part because of his heroism at Bull Run: the story ran that he had led the men in battle and had received strong kudos from General Longstreet himself. The problem was: the story was an extreme exaggeration. While he was commended after the battle for acting as a field officer and “render[ing] me all the assistance in his power” by the Fifth’s Lieutenant Colonel, J. P. Jones, there is no actual record of him being commended by Longstreet. Besides, as Jones wrote in the same report, the Fifth had done nothing more at Bull Run than a bit of skirmishing.

The Thirty-fifth, in their

biography, noted the falsity of the story and their disgust with Sinclair.

Newspapers were no kinder to him, calling him a coward and a traitor. It was

not long until he resigned from the Confederate services.

The most interesting part of this

tale is that Sinclair was at heart a unionist. Born in Scotland and trained in

Pennsylvania, he was a Presbyterian minister who had preached a sermon his

congregation found too abolitionist. His parishioners were so disturbed that

they threatened to lynch him. Relatives advised him to join the Confederate

army to protect his family. He would testify to Congress after the war that he

had done so against his will. “Have you ever willingly done any act to promote

the rebellion?” he was asked at this hearing. His answer: “Not willingly.”

One historian declares that Sinclair went so far as to sign on as chaplain for a Union regiment before the war ended, declaring him "a notorious figure in the Reconstruction."

This column originally ran in three parts in the New Bern Sun-Journal on November 10, 17 and 24, 2008.

1862: Land Mines and Gabriel Rains

He spent his childhood in New Bern and moved on to bigger and deadlier things.

It was May 4th, 146 years ago, that (by proxy) a Yankee horse rider made Gabriel Rains’ acquaintance. It must have been emotional for him, because he went all to pieces. Literally. Rains, who had played with

booby-traps during his days, in the Seminole wars in Florida was overseeing the Confederate

retreat from Yorktown in May of 1862. Remembering those past times, he began

planting shells with pressure-activated fuses or trip-wires in and about the

town to catch his advancing enemy unawares. On May 4, 1862, a rider, possibly

scouting near the town, set one off. One source declares the fellow to have

been a Yankee; another declares it to have been a

civilian death. Toss your coin and choose your truth: such is history. A number of soldiers died from the mines in the next few days. Union

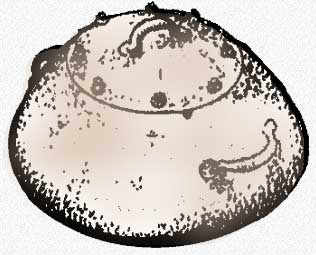

Brigadier-General William F. Barry described it: |  Above: A Civil War period land mine. |

Several of our men were injured by the explosion of what was ascertained to be loaded shells buried… a few inches below the surface of the ground, and so arranged… that they exploded by being trod upon or otherwise disturbed. In some cases articles of common use, and which would be most likely to be picked up, such as engineers’ wheelbarrows, or pickaxes, or shovels, were laid upon the spot with apparent carelessness. Concealed strings or wires leading from the friction primer of the shell to the superincumbent articles were so arranged that the slightest disturbance would occasion the explosion. (Official Records of the Rebellion)

A number of men were killed before

the method of their death was figured out.

Rains began to experiment with a

new fuse for his mines the following winter—he would lose a thumb and forefinger to his work. Slowly, he developed a highly-sensitive fuse that would continue to be

used until 1983. According to a landmine awareness webpage, several of Rains’

land mines were found in 1960 and were determined to be quite potent.

His invention lives on and is one

of the most controversial weapons in today. Twenty-four thousand people are

maimed or killed by landmines every year—one every 22 minutes. Most of these

victims are not soldiers.

Land mines were just as

controversial in the Civil War. General Barry again:

These shells were not thus placed on the glacis at the bottom of the ditch, &c., which, in view of an anticipated assault. might possibly be considered a legitimate use of them, but they were basely planted by an enemy who was secretly abandoning his post on common roads, at springs of water, in the shade of trees, at the foot of telegraph poles, and, lastly, quite within the defenses of the place—in the very streets of the town… I was myself a witness of the horrible mangling by one of these shells of a cavalryman and his horse outside of the main work upon the Williamsburg road, and also of the cruel murder in the very streets of Yorktown of an intelligent young telegraph operator, who, while in the act of approaching a telegraph pole to reconnect a broken wire, trod upon one of these shells villainously concealed at its foot. It is generally understood that these shells were prepared by General George W. Rains, of the Confederate Army, for his brother, Brig. Gen. Gabriel Rains, the commander of the post of Yorktown, at whose instigation they were prepared and planted. The belief of the complicity of General Gabriel Rains in this dastardly business is confirmed by the knowledge possessed by many others of our Army of a similar mode of warfare inaugurated by him while disgracing the uniform of the American Army during the Seminole war in Florida.

General Rains, a New Bern son, invented his gruesome devices as a means of overcoming vastly superior numbers. Perhaps, in the grand scheme of things the mines had no great military effect on the war—beyond the growing bitterness of Yankees who died by them and held guns on Confederate prisoners who dug them up and disarmed them.

One victim every 22 minutes. It’s a legacy to think about.

This column first appeared in the New Bern Sun-Journal on May 5, 2008.

| The gallant 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment storms Fort Wagner in South Carolina. A number of the white officers for this historic regiment were recruited from the 44th Massachusetts, serving in New Bern--among them Wilkie James, brother of the future novelist Henry James. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

What do movies, Negro regiments, a South Carolina fort and Henry James have in common? |

New Bern, of course.

I was thinking of this while I was watching the classic 1989 film Glory, about the ill-fated 54th Massachusetts, the first colored regiment recruited in the north during the Civil War.That regiment, formed in 1863, was officered by Robert Gould Shaw, young and affluent son of Boston abolitionists. Shaw, a Harvard man, was obligated to fill up his officer corps with whites. Naturally, he wanted men with experience—and men who shared his family's abolitionist views. Perhaps he and Massachusetts governor John Andrew consulted before Andrew decided to seek these officers through a nine-months regiment he knew of that was already in the field.

That regiment was the 44th

Massachusetts, whose men served their entire term in and around

the captured southern city of New Bern, North Carolina. A regiment of

wealthy young men, many of them were Harvard students looking for heroic adventure.

Colonel Lee, the commanding officer, received a letter on Feb. 18, 1863,

seeking potential officers. Several 44th men responded, and some would sacrifice their lives at the battles of Fort Wagner and Honey Hill.

Most of these recruits were from

the elite Company F: Cabot Russel, a

sergeant was one; William Simpkins, a private, was another.

Then there was their friend

Sergeant Garth “Wilkie” James. He was the son of Henry James Sr., promoter of a theology known as Swedenborgianism. Wilkie’s more famous brother was Henry

James Jr., who would ultimately leave America to live in Europe and write such

books as Daisy Miller and The

Turn of the Screw, those books—as Woody

Allen once spoke of the classics—“that we all love and avoid.”

Wilkie, who was only 17 when he

signed up, was no soft-boiled abolitionist. He believed that “slavery was a

monstrous wrong, its destruction worthy of a man’s best effort, even unto the

laying down of his life.”

The chosen men were mustered out

of their regiment and shipped to Readville, Massachusetts, where they set

about training the experimental army of African Americans. It must have been a bit of

an old-home day for them, for this was the very camp where the 44th

had done trained.

Wilkie, his pals Cabot and

William and the other officers formerly of the 44th in New Bern

marched at the fore of their men when they left Boston on May 28, 1863. The

regiment found itself doing manual labor for some time but finally saw is first

action on James Island, SC, on July 16.

They carried themselves well, won the fight, and paid a price of 42

casualties.

Two days later they marched into

history in the ill-fated assault on Battery Wagner, a well-armed fort guarding

the approaches to Charleston. If you have seen the movie, you know the ultimate

result: if you have not, then by all means rent it and learn.

Russel and Simpkins would be

among the enormous casualties in the assault, dying near Colonel Shaw. Wilkie

would survive, but only just. He once described his part in the fight to a

fellow officer: “When we received the first discharge of the enemy’s cannon [I

gathered] together a knot of men after the suspense of a few seconds, I waved

my sword for a further charge towards the living line of fire above us. We had

gone then some thirty yards, but determinedly onwards, the ranks obliquely

following the swords of those they trusted.” He was wounded in the side by a

shell, but kept going. Then a canister ball hit his foot, an injury that put

him out of the action. He dragged himself some distance until he was found and

rescued. After the battle he returned home to recuperate.

His injury was bad enough that he

resigned in July of 1864—but his heart was big enough that he found a way back

into the 54th at the end of the year. The wound would continue

harassing him the rest of his life.

Wilkie was the passionate member

of the family—of his brothers, one would be a high-brow, intellectual writer and the other a

Harvard professor. Wilkie was certainly no bad fellow to have a connection with our town.

This column first ran in the New Bern Sun-Journal on August 18, 2008.

1864: The burning of the Gunboat Underwriter.

They called Captain Jacob Westervelt’s ship the Underwriter, but after the Confederacy got through with her the name Underwater would have been more appropriate. Or the All-over-the-water. She was a Federal gunboat, a side-wheel steamer anchored at New Bern in defense of the Union-held town. Occasionally she forayed down the Neuse and up the sounds, making herself a pariah to her Confederate foes. Poorly-defended New Bern had fallen in March, 1862, and her blue-coated captors lost no time in turning the place into a heavily-armed camp. Soldiers were brought in by the thousands, gunboats plied the waters and earthwork forts appeared like mounds built by mutant prairie dogs. One, Fort Totten, was cleverly disguised to look like a playground. Oh, wait. It is a playground--today. But back then it was lethal: steep earthen walls behind which scowling soldiers and very big guns lay waiting. Had the Parks and Recreation Department had its way, I’m sure such nonsense would have been stopped. |  John Taylor Wood, Confederate commander of the Underwriter expedition in 1864. Courtesy of the U. S. Naval Historical Center, Washington, D. C. |

By 1864, the town was well-entrenched. But the Confederacy noted that the town’s store of supplies would go mighty fine under the Stars and Bars. Robert E. Lee, doubtless suspecting the town was a little over-sure of itself, suggested to President Jeff Davis that, perhaps, New Bern was ripe for a fall. Jeff concurred.

But a land battle could not be won

if the Yankees had gunboats in place. The Underwriter needed to be put out of commission – or, better yet,

put into Confederate commission. It would take a daring band to capture a ship

from the very jaws of a Union stronghold. Jeff knew just the man: his nephew,

John Taylor Wood.

Wood was known for daring raids on

Union shipping – he’d burned his share of boats, and had commanded the Tallahassee, destroyer of 26 Union vessels in her brief career.

Wood had no gunboats to launch. His plan was simple and daring: ten small boats with a dozen men each would row down the fifty or so miles down the Neuse from Kinston to a point across the river from where the Underwriter was moored, then turn and attack it in the early hours of February 2. The men would storm the craft, boarding it with small arms, using the element of surprise to overrun the crew and capture the boat. Then they would stoke the engines and turn the ship against her former owners.

To Woods's advantage, only three gunboats were guarding the town that night--"inferior boats" in the words of Union Brigadier-General I. N. Palmer: the Commodore Hull and the Lockwood. Against them was the fat that the gunboat was moored between three strong Union forts.

The Confederate naval surgeon

Daniel Conrad was among the sailors chosen for the secret mission. Ten small

boats and one hundred and twenty men would take part, “every one of whom were

young, vigorous, fully alive and keen for the prospective work,” the surgeon

would recall twenty-five years later.

They embarked down the Neuse River

from Kinston on a Sunday, February 1. At sundown they encamped on an island,

and “in distinct and terse terms” heard their instructions from Commander J.

Taylor Wood—a naval officer known for daring exploits of this kind. The plan

was simple: after a down-river sail of sixty miles the ten boats would board

the Underwriter from two sides. Using

small arms and surprise to capture her, they would build up her steam, loose

her moorings and sail her away.

Dr. Conrad recalled that

Commander Wood “thereupon… offered up the most touching appeal to the Almighty

that it has ever been my fortune to have heard… it was the last ever heard by

many a poor fellow and deeply felt by every one.”

Under cover of night, they sailed

on. Among those sailors was at least one New Bernian, Captain David Sermonds

who had a post of some honor, pilot on Commander Woods’ own boat. This

according to Col. John Whitford, a New Bern historian who had taken part in

that war.

The warriors passed two points

where Union pickets were suspected, and sat on their oars, drifting in silence,

undiscovered. Around 3:30 in the morning they arrived in New Bern and searched

cautiously for their prey, using the city’s lights to guide them. Though they

searched, even daring to approach close to some wharves, “Not a gunboat could

be seen,” Dr. Conrad said. “None was there.” Eventually the rising sun joined

the Union cause, forcing the saboteurs to seek shelter on an upstream island to

wait out the day.

During that day, help came from

unexpected quarters—both Confederate and Yankee. In the occupied town,

Brigadier-General I. N. Palmer advised that the Underwriter be moved to “an advanced position in the Upper

Neuse” (his report as cited in the War of the Rebellion official records). This set the boat in easy

reach—about five miles from the island, though still within protective range of

Union forts on land. Captain Westervelt followed these, the last orders he

would receive in this world.

The Confederate sailors watched

with happy amazement as the side-wheeled gunboat steamed into view about

sundown. Soon after a large launch with fifteen men and a howitzer appeared as

additional aid.

At about 9 p.m. the sailors started

their final approach toward their prey.

A dozen confederate launches pulled

slowly and cautiously down the Neuse River toward town. Commander J. Taylor

Wood sat in his boat, watching the floating bulk that was his target, the Underwriter, grow slowly closer in the dark. With him was his

coxswain, Captain David Hassell, who had served with him on the Tallahassee, a successful privateer that had done much damage to

Union shipping.

It would take them four hours to

row the five miles to the east side of the river opposite the Underwriter. There, they angled their boats for the ride across,

hoping they would reach her side before being found out.

Colonel John Whitford, a

contemporary and New Bern historian, described the raid as told to him by

Hassell, who was his friend:

“Finally opposite

the enemy’s vessel the turn is made and the command ‘pull for the ship boy’s

and your life’ rings out. In a moment the Underwriter’s sides are all aflame in

the dark night, and the water shake and the air roar with her guns. Captain

Wood looks back: ‘Steady, steady!’ and ‘Pull, boys, pull!’ are his only words.

The dead and dying in the boat are not heeded. One lies between the coxswain’s

feet, yet the helm is held with unflinching grasp. On, on, the boats rush.

Another volley and more dead and wounded.”

The mission’s surgeon, Daniel

Conrad, had bloody tales to tell of the boarding of the craft. His own boat was

slated to be the first to board but its coxswain was shot dead, a bullet

between his head. Another boat under one Lt. Loyall touched the Underwriter first, and its men piled on. Lieutenant Loyall,

being nearsighted, tripped and fell as he hit the boat; the four men following

behind him were shot dead by the defending crew. Dr. Conrad found the deck slick

with blood; he was led by a comrade to assist a wounded youth whose head, he

discovered to his horror, had been cleaved in two, vertically, with a sword.

Hassell would recall one

midshipman, climbing aboard from his boat, having his head severed from his

neck and “fall[ing] on the deck before his body does.”

Bodies fell rapidly on the other

side as well: a union report would claim all but five of the crew on board were

killed or captured. Captain Westervelt was shot in the leg; he tumbled

overboard and would not be seen again until his body would wash up on shore

some days later.

Violence has a short attention

span: in five minutes’ time the ship was in Woods’ hands. Engineers quickly set

themselves to the task of warming up the boilers. Other sailors split their

duties between guarding prisoners, preparing to hold off additional defenders,

and trying to loose the boat from the wharf. But time was against the gallant

crew: already Fort Stevenson on shore was angling her cannon and riddling the

craft with musket, grape and solid shot. The sidewheeler’s walking beam was

soon disabled.

Meanwhile, Commander Woods received

other bad reports: the boiler’s fires had completely cooled and would take at

least an hour to build up steam; heavy chains connecting the boat to a buoy

would also require hours of work. Reluctantly, he gave the order to fire the

ship.

The sailors abandoned the craft,

taking their dead and some prisoners with them then lay on their oars while

officers set fire to the lower decks. As they rowed away they watched the Underwriter light the night until its powder rooms ignited,

filling the air with the Fourth of July and toothpicks and splinters.

In the long-term, there was little

military significance to the raid. The city was left with two “inferior boats”

(General Palmer’s words), but others would soon be added. But it showed that

Dixie, though by this point out-gunned and out-manned to a hopeless degree,

still possessed all the spunk and courage that makes her descendants so proud

today.

This article originally appeared as a three-part column in the New Bern Sun-Journal on February 4, 18 and 25, 2009.